I. Executive Summary

The U.S. is experiencing one of the most severe cost-of-living crises in decades, and what began as a pandemic shock has created repercussions affecting younger Americans disproportionally. Although inflation has already started to cool from its 2022 high, essential costs such as transportation, housing, and debt payments have remained higher than before the pandemic, putting pressure on young workers, students, and first-time renters.

This brief examines how persistent inflation, rising debt, and a national housing shortage are shaping Gen Z’s economic future. It focuses on three critical issues: the rapid growth of youth debt, the ongoing housing supply gap that is pushing rents higher, and short-term policymaking that fails to consider longer-term generational equity. After highlighting previous efforts in monetary, fiscal, and housing policy, the brief proposes solutions to expand the housing supply through zoning reform, offer targeted relief to young adults facing high costs, improve student loan and credit policies, and ensure future policymaking accounts for generational impacts.

II. Relevance/Background

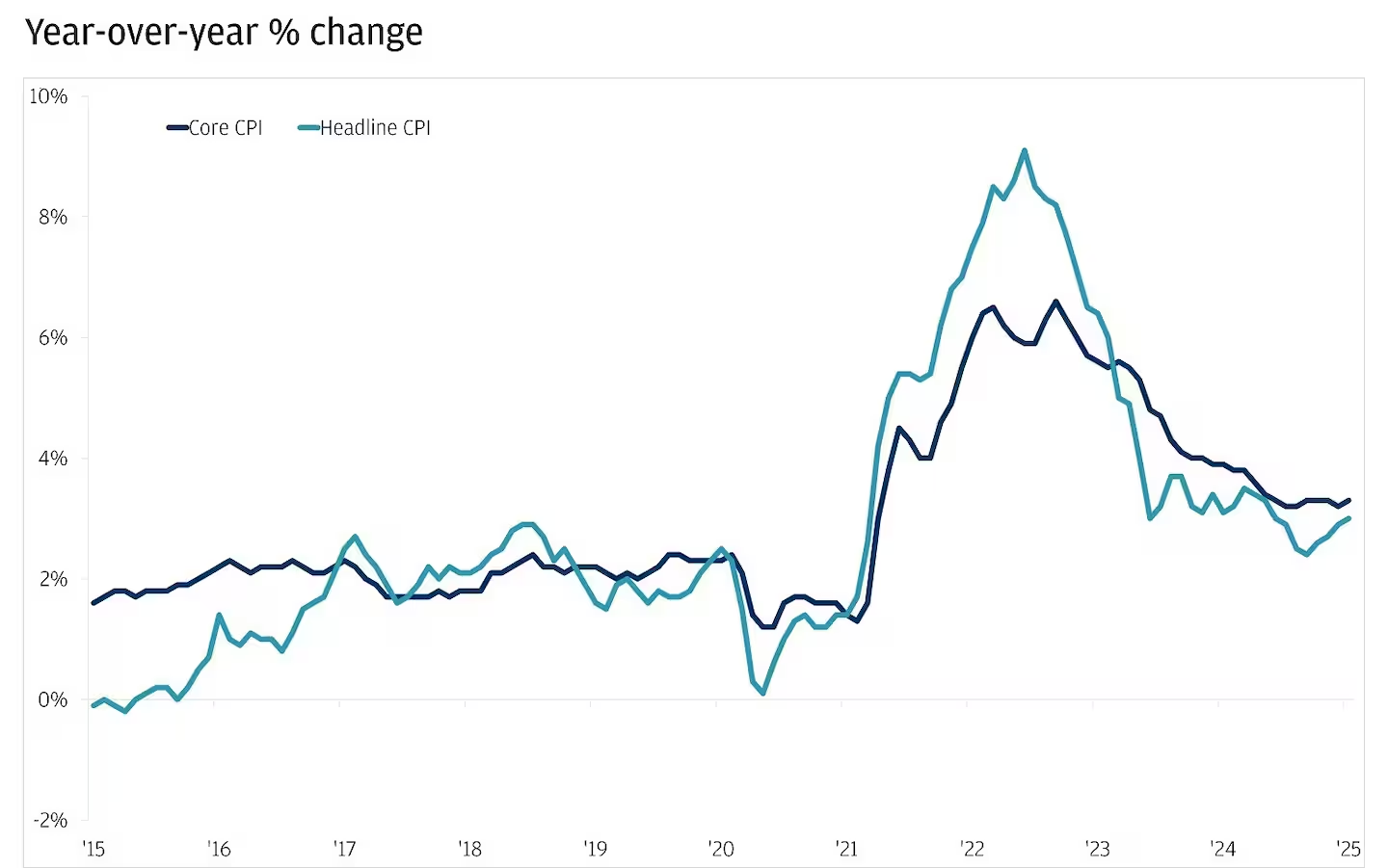

The current U.S. cost-of-living and housing affordability crisis has evolved rapidly since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and now presents structurally entrenched challenges for younger Americans, particularly Gen Z. At the outset of the pandemic, headline inflation remained modest (~1-2%), but as government stimulus surged, supply-chain disruptions deepened, and demand rebounded, inflation accelerated sharply; the annual change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose to approximately 8% in 2022. Headline inflation refers to the overall rate of price increase across the entire economy, capturing changes in the cost of goods and services at the aggregate level. The Consumer Price Index, published monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is the principal measure used to track inflation, reflecting how the prices of a representative “basket” of goods and services change over time and serving as a benchmark for policy and wage adjustments.

While inflation was initially framed as a temporary spike, the persistence of elevated costs for housing, shelter, and other essentials signals a deeper shift where housing and debt-service burdens have grown faster than incomes across the country. For example, more than 90% of U.S. counties saw median rents and housing prices rise faster than median incomes between 2000 and 2020. Since 2020, the rental market has remained particularly strained; from April 2020, the typical U.S. apartment rent climbed by 28.7%. Meanwhile, median household income grew by only ~22.5% over the same period. The most recent national report finds that nearly 31.3% of U.S. households were cost-burdened in 2023 (cost-burdened defined as spending more than 30% of income on housing), including nearly half of renter households.

These trends reflect a convergence of monetary, housing-market, and fiscal forces. On the monetary side, ultra-low interest rates and massive fiscal stimulus during the early pandemic years amplified demand while input-side shock waves, including labor and supply-chain constraints due to pandemic regulation, constrained effective supply, fuelling higher overall inflation and elevating borrowing costs once the Federal Reserve began tightening. At the same time, housing supply has long failed to keep pace with demand; the National Low-Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) estimates a rental-home shortage of roughly 8 million units for low-income renters. The current administration has sought to ease some of these pressures through targeted housing-supply initiatives and efforts to curb rent-inflation, which signal recognition of the crisis but have not yet reversed the underlying supply-demand imbalance. The resulting shortage has driven up both rents and purchase-prices even as wage growth has stagnated. While political parties’ stance on addressing the issue varies – Democrats generally advocate expanded public investment and housing assistance, while Republicans emphasize deregulation and tighter fiscal discipline to curb inflation – there is generally bipartisan consensus on the crisis’s urgency.

For Gen Z, these dynamics present an acute challenge. Entering the labor market with stagnating real wages and heightened cost burdens, younger Americans face squeezed budgets even before factoring in home-ownership aspirations. The mismatch between persistent housing cost growth and flat incomes has transformed what began as a short-term inflationary surge into a lasting affordability crisis – one that threatens equity and long-term economic mobility.

III. Policy Problem

The current cost-of-living crisis represents a structural challenge that is disproportionately affecting Gen Z. Facing the combination of high debt, an unaffordable housing market, and inadequate policy framework, young adults have become disconnected from long-term generational equity. Although headline inflation has receded from its peak in 2022, the most durable impacts have been felt in two areas key for early financial stability: the cost of borrowing and the housing market. These are not simply effects of a temporary inflationary surge, but indicators of deeper systemic imbalances that conventional policy tools have been slow to correct.

First, Gen Z is entering the economy at a time of unprecedentedly high borrowing costs and record levels of debt exposure. After more than a decade of historically low interest rates, the Federal Reserve’s rapid cycle of tightening monetary policy raised the federal funds rate to its highest range in over two decades. This has already increased the cost of student loans, auto loans, credit cards, and mortgages (Board of Governors). Young borrowers disproportionately rely on credit to bridge early-career wages, but now now face higher monthly payments, reduced purchasing power, and weakened pathways to build savings. Unlike older generations, who accumulated assets during periods of lower credit costs, Gen Z are beginning their financial life cycle under tighter constraints with diminishing room for upward mobility (Federal Reserve; Education Data Initiative).

Second, the housing affordability crisis has transformed from a cyclical market challenge into a generational mobility barrier. The persistent inconsistencies between housing market supply and demand, compounded by soaring rents, restrictive zoning, and stagnant real wages, has pushed homeownership further out of reach. From 2020 to 2024, typical U.S. rents increased by nearly 29%, while median household income rose far more slowly, leaving nearly one-third of American households cost-burdened and almost half of renter households spending more than 30% of their income on housing (U.S. Treasury; Pew Research Center). For young adults, the traditional markers of financial stability, like leaving home, renting, and eventually buying a first home, have shifted from expected milestones to far-off aspirations.

Finally, there is a widening policy gap between short-term inflation management and long-term generational equity. Recent monetary tightening effectively moderated price growth, but it did not address structural housing shortages or the rising debt-service burdens borne by young adults. Pandemic-era fiscal relief provided temporary stability but was not designed to ensure long-term affordability once emergency measures expired. As a result, Gen Z inherits the residual effects of each crisis: higher borrowing costs, elevated rent levels, and limited access to assets that shape lifetime economic opportunity (Board of Governors).

The issue at hand is not simply that Gen Z faces high prices, but that the current policy infrastructure was not built to confront the long-term distributional consequences of inflation on generational mobility. Without intentional reforms that align monetary, fiscal, and housing policy with modern realities, the cost-of-living crisis will evolve into a structural barrier to mobility for generations to come. Thus, this analysis underscores the need for durable reforms that can stabilize affordability, expand access to opportunity, and rebuild generational resilience.

IV. Tried Policy

Over the past several years, the United States has relied on a combination of money tightening, fiscal relief, and housing subsidies in order to manage economic instability and rising living costs. The following policy tools were deployed rapidly in response to the pandemic and the subsequent inflation surge, shaping the economic landscape that Gen Z entered as students, workers, and first time borrowers.

A. Money Tightening

To curb the rapid rise in inflation in 2021-2022, the Federal Reserve launched one of the most aggressive interest rate hiking cycles in decades, raising the federal funds rate from 0-0.25% in March 2022 to 5.25-5.50% by July 2023, increasing borrowing costs across the economy. These rate increases helped to slow overall price growth from a peak of 9.1% in June 2022 to under 4% by mid-2023 by stimulating demand and stabilizing inflationary expectations. However, they simultaneously increased the cost of borrowing for mortgages, student loans, auto loans, and credit cards. For Gen Z – who are disproportionately new entering new credit markets – higher rates heightened debt burdens and pushed homeownership even further out of reach, limiting early wealth building opportunities relative to previous generations.

B. Fiscal Relief Measures

Pandemic-era fiscal policy aimed to prevent a severe economic collapse. Three rounds of federal stimulus payments – $1,200 in 2020, $600 in early 2021, and $1,400 in 2021 – provided households with immediate cash to help offset lost income. These direct payments, combined with greater unemployment insurance, enhanced Child Tax Credit benefits, and supporting small businesses such as the Paycheck Protection Program, helped households and families maintain spending through significant income shocks. Together, these tools were successful in softening the recession and supporting increased consumer demand. The temporary federal pause on student loan payments also gave Gen Z some financial breathing room, particularly for young borrowers whose wages were not rising as quickly as the cost of living.

At the same time, the scale and speed of this relief, paired with supply chain disruptions, contributed to inflationary pressure as demand quickly outpaced constrained supply. With millions of Americans receiving stimulus payments and enhanced unemployment benefits, demand for goods and services rebounded faster than businesses were able to restore production; real personal consumption expenditures rose by about 8% between March 2021 and March 2022, one of the fastest increases in decades. Global shipping delays, factory shutdowns, and labor shortages kept supply constrained, only creating the conditions for prices to rise further.

C. Housing Subsidies and Rental Assistance

Housing subsidies and rental assistance during the pandemic sought to prevent mass displacement and stabilize rent burdens. Federal Emergency Rental Assistance programs and expanded Housing Choice Vouchers helped millions of renters remain housed despite income disruptions. Existing affordable housing tools, such as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) as well as federal housing trust funds, continued to support new development yet still remained insufficient relative to national supply shortages. While these measures mitigated immediate crises, they did not reverse long standing gaps between housing supply and demand. For Gen Z renters entering adulthood during a period of accelerating rent growth, these programs offered short term stabilization without altering long term affordability.

D. Policy Solutions

The current effects of inflation on Gen Z show the need for a two-track policy solution aimed at maintaining the state of affairs in the short-term and reforming the structure in the long-term. Despite the increase of rates by the Federal Reserve in 2022, thus mitigating headline inflation, the delay effects of its mechanisms on youth borrowing, housing affordability, and employment are unpleasant. Monetary and fiscal policy also ought to be altered as a preventive containment to proactive opportunity-building.

E. Provide more Housing Using Special Incentives and Zoning Reform.

The point of the affording crisis is short supply. Governments at the federal and state level can accelerate the construction by making contingent housing grants on the reforms and simplification of the approval procedures. The Housing Supply Action Plan of the Biden Administration and the Pro-Housing Community Pledge of HUD are both useful, but further adoption of inclusionary zoning, commercial space adaptive reuse, and federal tax credits of multi-family development is necessary to make the 8-million-unit gap. The partnerships between the government and the business are capable of harnessing the capital of the population on the one hand, and simultaneously addressing the needs of the locality.

F. Relief on Inflation To Younger, Low-Income Households.

The current relief systems such as generalized rebates on taxes fail to focus on those who are most at risk due to the rise in cost of living. The policymakers could devise age-specific and income-specific transfers such as refundable tax credits or an expansion of qualification to under-30 workers to EITC that would counter the regressivity of inflation without stimulating the economy overall. Temporary federal equivalent to state-based remuneration of rent stabilization plans or transport subsidies would also dampen young movement and labor availability.

G. Redo Credit and Student Loan Policy of Generational Equity.

Re-payments of student loans and high interest on loans have compounded Gen Z debt-loads. The credit system that is to be established should incorporate repayment limits that are inflation adjusted and ensure the borrowers are safeguarded against compounded interests more. Balancing the household balance sheets would be the increase of the volume of income repayment, and reevaluation of the bankruptcy levels on education loans. At the same time, the policymakers should increase the financial literacy and access to credit initiatives with the cooperation of the community colleges and youth associations.

H. Nurture a Generational Equity Lens Policy-Design Institutional.

Finally, creators of fiscal and monetary policy should have a generational analysis built into their policy appraisals estimating the disparity in the effect of rate increases and spending and tax cuts on various age groups. Long-term intergenerational tradeoffs would be brought into the limelight under the mechanism of the Youth Impact Assessment that relies on environmental impact review.

In short, effective adaptation will constitute the inclusion of structural supply reforms, particular fiscal relief, and generational responsibility. There must be price stabilization, but it is the policy agenda to ensure this reality for Gen Z.

V. Youth Impact

The persistent cost of living crisis, fueled by years of high inflation and insufficient policy response, poses an enduring challenge for Gen Z. For this group of people entering the labor market and establishing their financial footing, the economic stability has threatened long-term wealth accumulation, homeownership prospects, and overall economic mobility.

A. Long Term Consequences on Financial Milestones

Stagnant wages, coupled with increasing costs for essentials, leave younger Americans with tight budgets. This constraint limits their capacity to save, diminishing the crucial early-career period where investment gains can compound effectively. Furthermore, with housing prices and mortgage interest rates far outpacing wage growth, the median age for a first-time homebuyer has risen, pushing homeownership out of reach for many in their 20s and 30s. A striking 84% of Gen Z aspiring homeowners report delaying major life decisions until they can afford a home (Lake). The inability to build home equity, which has historically fueled middle-class wealth, ensures a lasting generational asymmetry, where younger people face greater obstacles in achieving long-term economic stability compared to their predecessors at the same age.

B. Social Milestones

Financial instability directly impacts social decisions. Many young Americans delay forming their own independent households, opting to live with parents—a trend that reached levels not seen since the Great Depression (Fry). Furthermore, a substantial percentage of Gen Z reports delaying marriage or having children due to the financial impossibility of supporting a family while simultaneously navigating student loan debt and saving for a home. This delay has significant ripple effects on demographic trends and broader economic consumption patterns.

C. Widening Intergenerational Inequality

The combination of student debt, wage stagnation, and the housing crisis acts as a systemic filter, accelerating the widening gap in wealth between younger and older generations. Older generations benefited from lower relative housing costs during their prime earning years, allowing them to accumulate significant home equity. Conversely, Gen Z is disproportionately burdened with high debt and high rental costs, preventing them from acquiring these same foundational assets. This disparity is particularly noted among young adults of color, who face a magnified impact from housing unaffordability, exacerbating existing racial wealth gaps.

D. Youth Activism and Policy Demand

Youth representation is essential to bridge the policy lag between short-term stabilization strategies and the long-term goal of generational resilience. When young voices are included, policymakers gain direct insight into how issues like inflation translate into real-world constraints on housing accessibility and family formation. The economic challenges have spurred a new wave of youth civic engagement focused on structural policy change. Instead of accepting the status quo, young activists are increasingly using technology and grassroots organizing to challenge housing injustice, demand land-use reforms, and advocate for structural interventions to stabilize the cost of living.

VI. Conclusion

The analysis presented across this paper illustrates that the contemporary cost-of-living crisis is not merely a transitory outcome of pandemic-era inflation, but as a result of underlying structural imbalances that disproportionately hurt Gen Z. While headline inflation has returned to more moderate levels, the cumulative impact of the phenomenon has been seen on high housing costs, increased debt-service burden and the lack of real wage growth, which has created a permanent affordability problem that conventional policy tools have been slow to resolve.

There are significant constraints in the policy responses that have been implemented so far. Monetary tightening has achieved the goal of taming aggregate price pressures but the transmission effect has been lagged resulting in strengthening borrowing constraints at a high point in the financial life cycle of young adults. The relief measures that were given were only enough to stabilize things in the short-term but the long-term gaps in housing supply, labor market inequalities and soaring credit were not significantly addressed. Combined with the trends, this has generated a generational asymmetry in which younger cohorts have experienced greater obstacles in accumulating assets and economic stability in the long term than their predecessors at similar ages.

What we are witnessing is a necessity to reset the policy back to generational resilience, rather than the cyclical correction. The housing stock needs to be increased, the credit and student-loan systems should be redesigned to be more indicative of labor realities in the twenty-first century, and aid should also be targeted at the youngest and most financially strained households, which is not an incidental improvement, but rather a precondition to restoring mobility and avoiding the further growth of intergenerational disparities. The use of a generational prism in fiscal and monetary policy would make sure that stabilization strategies will no longer be unevenly distributed among the individuals with the least wealth accumulated.

Finally, to protect the economic future of Gen Z, it is necessary to start viewing affordability as a long-term investment and not a one-time interference. It may be that inflation has calmed down, though its effects continue to be felt in terms of increased rents, increased debts, and adverse milestones. Policies that bridge this gap between short-term stabilization and long-term opportunity are essential if the next generation is to move from coping with crises to building lasting economic security.

VII. References

A Visual Guide to Inflation from 2020 through 2023 | Congressional Budget Office, www.cbo.gov/publication/60480.

“Rent, House Prices, and Demographics.” U.S. Department of the Treasury, 7 Aug. 2024, home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/rent-house-prices-and-demographics.

DeSilver, Drew. “A Look at the State of Affordable Housing in the U.S.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 25 Oct. 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/10/25/a-look-at-the-state-of-affordable-housing-in-the-us/.

“NLIHC Releases the Gap 2025: A Shortage of Affordable Homes.” National Low Income Housing Coalition, 13 Mar. 2025, nlihc.org/news/nlihc-releases-gap-2025-shortage-affordable-homes.

U.S. Opinions on Housing Affordability: A BPC/NHC/Morning Consult Poll | Bipartisan Policy Center, bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/opinions-on-housing-affordability-poll/.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Federal Funds Effective Rate — Historical Data. Federal Reserve, https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/openmarket.htm.

Congressional Budget Office. “A Visual Guide to Inflation from 2020 through 2023.” CBO, 2023, www.cbo.gov/publication/60480.

Education Data Initiative. “Student Loan Debt by Generation.” EducationData.org, 2024, https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-generation.

National Low Income Housing Coalition. The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes 2025. NLIHC, 2025, https://nlihc.org/gap.

Pew Research Center. DeSilver, Drew. “A Look at the State of Affordable Housing in the U.S.” Pew Research Center, 25 Oct. 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/10/25/a-look-at-the-state-of-affordable-housing-in-the-us/.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Consumer Price Index Summary – 2025 M08 Results.” BLS, 24 Oct. 2025, www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm.

Forbes Advisor. “Fed Funds Rate History.” https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/fed-funds-rate-history/.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED). “Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL.

Pandemic Response Accountability Committee. “Update — Three Rounds of Stimulus Checks: See How Many Went Out and to Whom.” https://pandemicoversight.gov/data-interactive-tools/data-stories/update-three-rounds-stimulus-checks-see-how-many-went-out-and-to-whom.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. “Economic Impact Payments: Assistance for American Families and Workers.” https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-american-families-and-workers/economic-impact-payments.

Acs, Gregory, and Laura Wheaton. “Inflation, Public Supports, and Families with Low Incomes.” Urban Institute. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/inflation-public-supports-and-families-low-incomes.

Catherine, Sylvain, Mehran Ebrahimian, and Constantine Yannelis. How Do Income-Driven Repayment Plans Benefit Student Debt Borrowers? 2024. https://www.nber.org/papers/w33059.

Hanson, Melanie. “Student Loan Debt by Generation.” Accessed November 5, 2025. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-generation?.

Horwich, Jeff. “Lower Income, Higher Inflation? New Data Bring Answers at Last.” Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2024/lower-income-higher-inflation-new-data-bring-answers-at-last?.

National Low Income Housing Coalition. “The GAP.” Accessed November 5, 2025. https://nlihc.org/gap?.

“A Staggering 84% of Gen Z Say They’re Delaying Milestones to Buy a House: There’s ‘No Single Fix’ for the Affordability Crisis, Real Estate Exec Says.” Fortune, 10 Nov. 2025, fortune.com/2025/11/10/gen-z-delaying-milestones-housing-affordability-crisis-no-single-fix/.

Fry, Richard, Jeffrey S. Passel, and D’Vera Cohn. “A Majority of Young Adults in the U.S. Live with Their Parents for the First Time Since the Great Depression.” Pew Research Center, 4 Sept. 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/09/04/a-majority-of-young-adults-in-the-u-s-live-with-their-parents-for-the-first-time-since-the-great-depression/.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.svg)

.svg)