I. Abstract

Foreign assistance plays a critical yet complex role in global development. This paper examines foreign funding as both a potential driver of long-term growth and a possible source of dependency, drawing on historical and contemporary examples of U.S. aid. Employing both quantitative and qualitative analysis, we assess how different aid modalities (direct budget support, project-based financing, security and diplomacy assistance, and public-private partnerships) shape outcomes in partner countries.

The demographic transition model is also used as a framework for identifying the most effective investments, from early stage health and education interventions to later stage infrastructure and institutional reforms. Special attention is given to the implications of foreign aid for young people, who often face both immediate and long-term consequences of donor decisions.

Our findings are twofold. Firstly, qualitative analysis reveals that the design of aid programs often matters more than the volume of aid provided; when strategically deployed, foreign funding can accelerate development and stabilize fragile contexts. However, its success is contingent on institutional strength, political will, and the avoidance of dependency traps. Secondly, quantitative analysis demonstrates that internet access should be the greatest funded sector for a developing nation given its largest influence on the economic mobility of a country relative to other sectors.

II. Introduction

Foreign assistance has evolved from an instrument of postwar reconstruction into a multifaceted portfolio encompassing development, humanitarian, and security investments. Its contemporary history is often dated from the European Recovery Program, commonly called the Marshall Plan. Between 1948 and 1952, the United States appropriated approximately $13.3 billion to reconstruct Western Europe's economies and institutions, hastening recovery and stabilizing allied democracies in the aftermath of World War II.

Since then, donor cooperation has been institutionalized through the OECD's Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and the convention that affluent states should remit a proportion of national revenue to development. Even so, aid resources are scarce and politically contentious. In 2023, DAC members’ official development assistance reached $223 billion, a record level representing 0.37 percent of their combined national income. However, fewer than a dozen countries exceeded or approached the 0.7 percent threshold. Recent reductions or reprofiling by larger donors also reflect domestic and fiscal pressures. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the government reduced aid from 0.7 to 0.5 percent in 2021, showing that even committed donors have trade-offs.

The United States is the world’s largest bilateral donor in absolute figures and has spearheaded thematic programs that link money to outcomes. For example, the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief reports more than 25 million lives saved and millions of infections averted since its conception in 2023, demonstrating that sound health investments can yield exceptional human and economic returns by saving families, workforces, and future productivity. Additionally, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, formed in 2004, marries huge, time-limited grants with governance and policy requirements. By investing in infrastructure and institutional reforms, they spur development, their compacts now reaching dozens of countries. Aside from these flagship programs, the U.S. also offers assistance through basic education, agriculture, energy, democratic governance, and humanitarian assistance sectors, with disaggregated figures becoming increasingly available in open dashboards for public examination and comparative analysis.

There is no nation that has a limitless supply of foreign aid resources, so every dollar has its opportunity cost. Here, the demographic transition model offers a useful structure for sectoral ordering of priorities for countries at each stage of the model. Historically, early-stage environments have gained the most from investments on reducing child and maternal mortality and expanding basic education, whereas later-stage environments benefit from productivity-increasing infrastructure, human capital deepening, and capital market development that drive structural transformation. Evidently, sector choice and sequencing are as critical as scale.

This brief therefore asks the question: when the United States supports a partner country, what sector should receive the marginal dollar to maximize long term national progress, and under what conditions is that decision likely to succeed?

III. Methodology

We use a quantitative approach to our analysis by applying a multivariate linear regression to determine which sector of a developing nation most strongly influences its economic and social mobility (i.e., determining which sector to allocate money to for maximum return on investment).

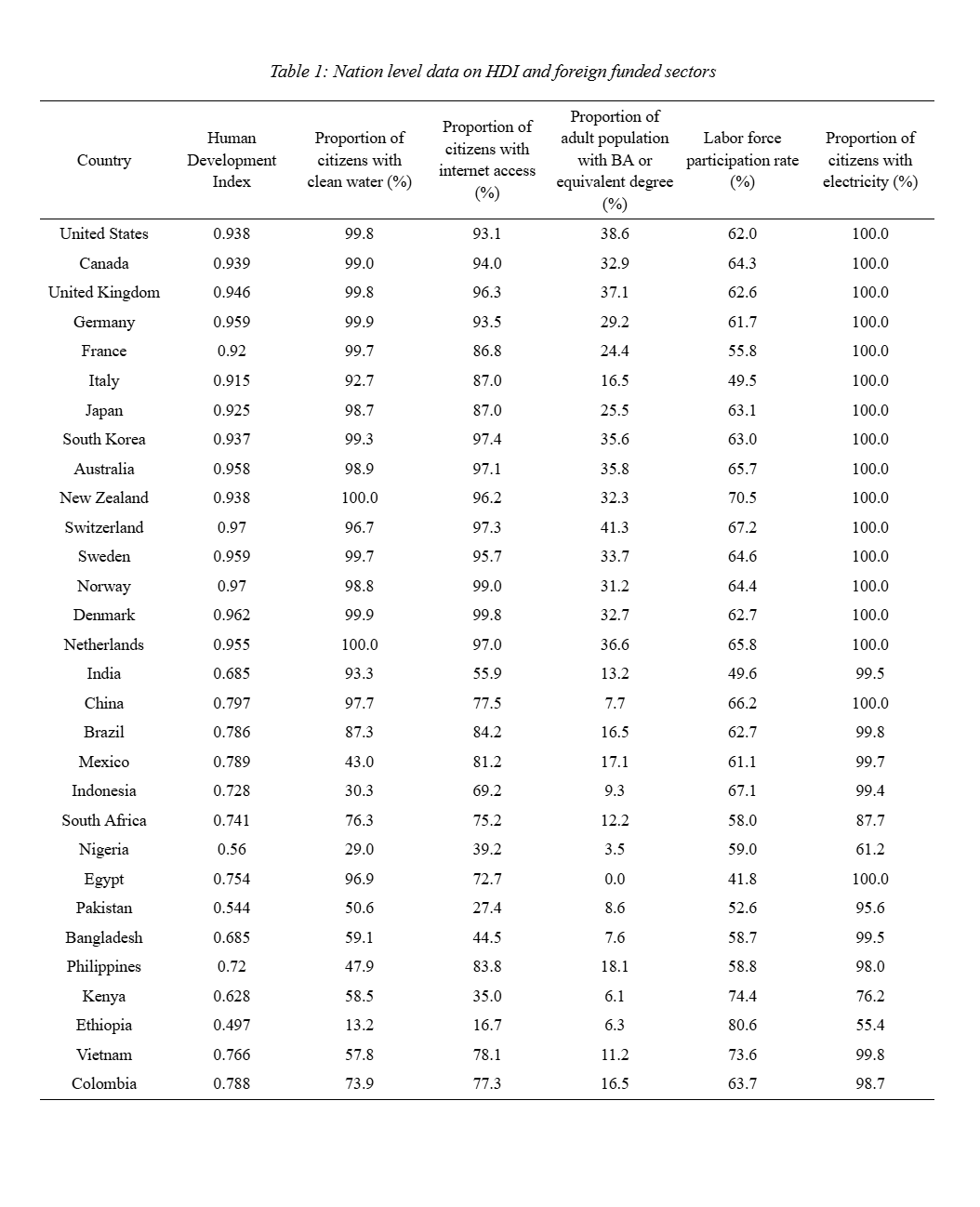

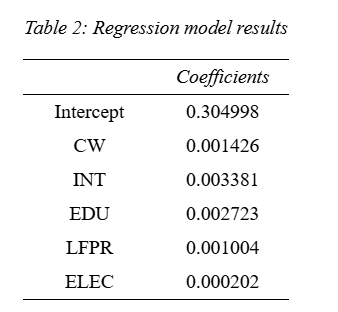

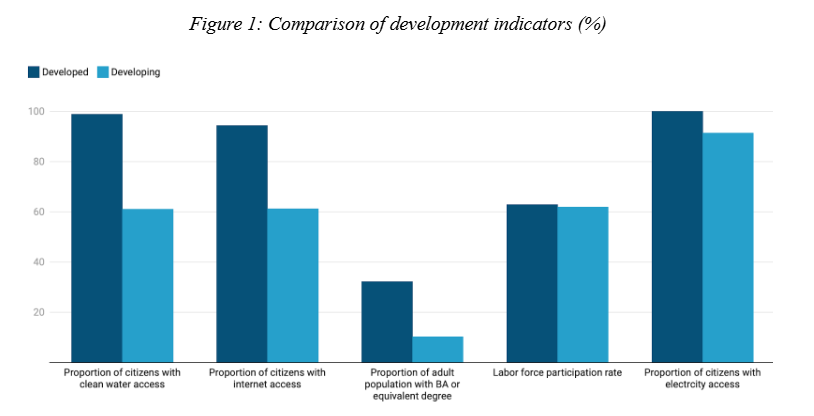

We build our model through gathering data from 30 nations: 15 developing and 15 developed. To quantify the economic and social status of the countries, we use its Human Development Index (HDI) (see Table 1). We select five sectors to determine which has the greatest impact on HDI: 1) proportion of citizens with clean water access, 2) proportion of citizens with internet access, 3) proportion of adult population with BA or equivalent degree, 4) labor force participation rate, and 5) proportion of citizens with electricity.

In this model, a weighting factor is assigned to various independent variables, and used to predict the dependent variable, the HDI.

After running the regression, we obtain coefficients for each explanatory variable. The variable with the largest coefficient (i.e., the variable with the greatest influence on the HDI) represents the sector where foreign funding should be prioritized (see Table 2).

IV. Results and Discussion

Quantitative Results

In running the multivariate linear regression model, we are provided with the coefficients of our independent variables. For clean water access, for example, the coefficient was 0.001426 which implies that a one percentage point increase in the proportion of people with access to clean water increases the nation’s HDI by 0.001426. Among the five sectors analyzed, internet access had the highest coefficient (i.e. the greatest impact on HDI for a one percentage point increase). Subsequently, given the scarcity of money allocated for foreign funding, we believe that expanding internet access across developing countries would provide the greatest return on investment. Conversely, given that the lowest coefficient was for the electricity sector, we recommend diminishing the money allocated to increasing the proportion of citizens with electricity as, we find, it yields the lowest return on investment in hopes of improving the nation's HDI.

We also note that the data highlights significant disparities between developed and developing countries across several key indicators of social and economic development (see Figure 1). Developed countries show near-universal access to essential services, with 98.9% of citizens having clean water, 94.5% having internet access, and 100% having access to electricity. In contrast, however, developing countries fall behind with only 61% having clean water, 61.2% with internet access, and 91.4% with electricity. We observe a sharp divide with education attainment: 32.2% of adults in developed nations hold a bachelor’s degree or equivalent, compared to just 10.3% in developing countries.

Despite these differences, we note that labor force participation rate is relatively close: 62.9% in developed and 61.9% in developing, suggesting that economic engagement remains similarly high across both groups and funneling money towards improving the LFPR of developing countries is not advantageous.

Policy Options

Countries channel foreign funding through a few main models, each with clear trade-offs. One is substantial direct contributions to a national budget in the form of grants or low-interest loans. This can finance major projects quickly: roads, electricity, schools, but may equally contribute to waste when the control and management is poor and cause a nation to become dependent upon external finance. The second method finances designated projects undertaken by ministries, development banks, or NGOs. Outcomes are simpler to monitor, but there is the risk of overlapping and even competing projects, which increase expenses and disorientation. A third direction dwells on security and diplomacy, training forces, exchange of intelligence, or even guarantees. This can establish stability that would then see the economy expand, but it may also end up drawing attention and money towards the social services. The fourth option attempts to crowd in private investment through guarantees or PPP. This approach would stretch taxpayer dollars, though it may leave governments with hidden liabilities or see profits flow abroad.

Design choices often matter more than headline volumes. Results-based contracts, open procurement, and independent audits reduce leakage. Local co-financing, time limits, and caps on how much aid pays for recurrent expenses help limit dependency. Where debt stress is high, grants or very soft loans with disaster-related “pause” features are safer. In fragile settings, funding should flex between relief and longer-term recovery; where capacity is stronger, donors can focus on durable systems—tax administration, civil-service training, and predictable regulations.

Impact on Young People

For youth in countries that receive funding, the gains can be direct and visible. Education funding can construct classrooms, educate educators, and increase internet connectivity, enabling students to remain enrolled in school and attain more knowledge. Health and clean-water initiatives enhance nutrition, prevent illness, and enhance early-childhood progress. New roads, power lines and transit help to reduce the time needed to go to school and work. The transition between school and first job can be facilitated by skills training, internships, and support of small businesses. However, there are dangers: the money will come in bursts so services will go up and down, the projects will have to be funded by other types of government organizations, and the problems with an increased cost will appear before the families.

For youth in donor countries, effects are indirect but meaningful. The money used to pay aid is public money and could impose an increased tax on the parents or a reduction in funding of other local programs affecting the family budgets and activities of children. Meanwhile, targeted aid reduces global risks like pandemics, conflicts, or refugee crises, which could otherwise have spillover effects, disrupted lives at home. It also provides students with opportunities to participate in exchange making, research, and service opportunities that develop strength and civic intent. Over time, as aid contributes to the expansion of new markets overseas, it may serve as support in home-based jobs and internships in the export industries.

V. Limitations and Conclusion

While foreign funding can encourage economic and social development, its effectiveness is often constrained by several key limitations. A primary risk is dependency, where recipient nations become over-reliant on external financing. This can stifle domestic innovation and sustainable self-sufficiency. Another challenge is volatility, as aid flows often shift with donor states’ political priorities, destabilizing programs reliant on consistent financing. This leads to service disruptions and increased hardships for families, particularly for youth who benefit from educational or health initiatives. Governance also poses a significant challenge. Weak oversight can lead to corruption and mismanagement of foreign funding (5). Furthermore, the specific delivery method introduces its own trade-offs. Project-based funding, for example, can create a fragmented landscape of overlapping and competing initiatives, which increases costs and reduces overall effectiveness.

In our quantitative analysis, several limitations emerge. First, our sample coverage is relatively narrow, sourcing data from only 30 of the over 180 nations in the world. Further research should, we recommend, incorporate a more robust dataset with a broader global coverage. And secondly, while we recommend allocating funding towards expanding internet access–given that it has the highest coefficient value–our model does not incorporate the differing financial costs for increasing our independent values by one percentage point. Further research should quantify these costs to produce a more accurate model.

Despite these limitations, our model performed strongly in predicting the HDI of a nation, given our selected input factors, leading to a Multiple R value of 0.979. Our analysis suggests that well-designed aid programs remain a powerful instrument for fostering growth and stability, particularly when tailored to a country’s stage of development. The demographic transition model highlights that early investments in health and education yield high returns in low-income contexts, while infrastructure and institutional reform drive productivity in more advanced states. Ultimately, the effectiveness of foreign funding is not determined by its sheer volume but rather by strategic choices regarding how and where it is allocated. When the United States directs its dollar toward sectors aligned with another country’s stage of development, the impact is significantly amplified. The success of foreign aid lies in its ability to foster durable systems and institutions, enabling recipient nations to eventually finance their own development and achieve long-term self-sustaining national progress.

VI. References

Cavalcanti DM, de Oliveira Ferreira de Sales L, da Silva AF, Basterra EL, Pena D, Monti C, Barreix G, Silva NJ, Vaz P, Saute F, Fanjul G, Bassat Q, Naniche D, Macinko J, Rasella D. Evaluating the impact of two decades of USAID interventions and projecting the effects of defunding on mortality up to 2030: a retrospective impact evaluation and forecasting analysis. Lancet. 2025 Jul 19;406(10500):283-294. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01186-9. Epub 2025 Jun 30. PMID: 40609560; PMCID: PMC12274115.

Croghan TW, Beatty A, Ron A. Routes to better health for children in four developing countries. Milbank Q. 2006;84(2):333-58. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00450.x. PMID: 16771821; PMCID: PMC2690167.

Riddell, Abby, and Miguel Niño-Zarazúa. “The Effectiveness of Foreign Aid to Education: What Can Be Learned?” International Journal of Educational Development, Aid, Education Policy, and Development, vol. 48, May 2016, pp. 23–36. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.013.

CEPR. “Budget versus Project Aid: A Tradeoff between Control and Efficiency.” December 2, 2016. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/budget-versus-project-aid-tradeoff-between-control-and-efficiency.

“Open Knowledge Repository.” Accessed October 10, 2025. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/d60d7ecc-a53e-5915-9a76-d736951471f3.

World Population Review. “Access to Clean Water by Country 2025.” Accessed October 10, 2025. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/access-to-clean-water-by-country.

World Bank Open Data. “World Bank Open Data.” Accessed October 10, 2025. https://data.worldbank.org.

World Population Review. “Internet Users by Country 2025.” Accessed October 10, 2025. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/internet-users-by-country.

World Population Review. “Labor Force Participation Rate by Country 2025.” Accessed October 10, 2025. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/labor-force-participation-rate-by-country.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.svg)

.svg)