Introduction

In the digital age, the information disorder, consisting of misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (MDM), has become a pervasive challenge, posing serious threats to democracy, public discourse, and individual autonomy (Bannerman, 2020). Canada, like many other countries, faces a pressing need to address this issue through effective legal mechanisms (Kandel, 2020). This paper argues that Canada must confront the multifaceted legal challenges posed by MDM and develop comprehensive solutions to regulate it effectively. At the heart of this argument lies the recognition that the information disorder undermines the foundational principles of democracy, including the right to access accurate information and the ability to make informed decisions (Kandel, 2020). In response, Canada must prioritize the protection of these principles by ensuring that its legal frameworks are robust and adaptable to the digital age.

Canada's Constitution enshrines fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, which must be carefully balanced against the need to prevent the spread of false information. Regulatory measures must therefore be carefully crafted to respect these rights while also safeguarding the public interest. Existing legal frameworks in Canada, such as Section 181 of the Criminal Code, The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, provide a foundation for addressing information disorder by establishing standards for truthfulness in public communications, regulating broadcasting content to ensure accuracy and fairness, and safeguarding the right to freedom of expression while achieving equilibrium with other societal values such as the protection of individuals from harm caused by false or misleading information (Bannerman, 2020). However, they need to be updated and strengthened. New legislation or amendments to existing laws are necessary to provide authorities with the tools they need to combat information disorder effectively. International perspectives also play a crucial role in shaping Canada's approach to regulating MDM. As a global community, it is imperative to draw lessons from the experiences and regulatory frameworks established in various jurisdictions to develop effective strategies. By analyzing approaches taken by other countries, including the US, EU, and the UK, Canada can gain valuable insights into what works and what doesn't in the fight against information disorder. Emerging regulatory strategies, such as those involving technology platforms, also offer potential solutions to the problem of MDM.

This paper argues that in response to the proliferation of information disorder in the digital age, Canada must address multifaceted legal challenges and develop comprehensive solutions to regulate MDM effectively. By analyzing existing legal frameworks, international perspectives, and emerging regulatory strategies, this paper aims to provide insights that can inform policy development and legal practice, thus safeguarding the integrity of information.

Information Disorder: Definitions

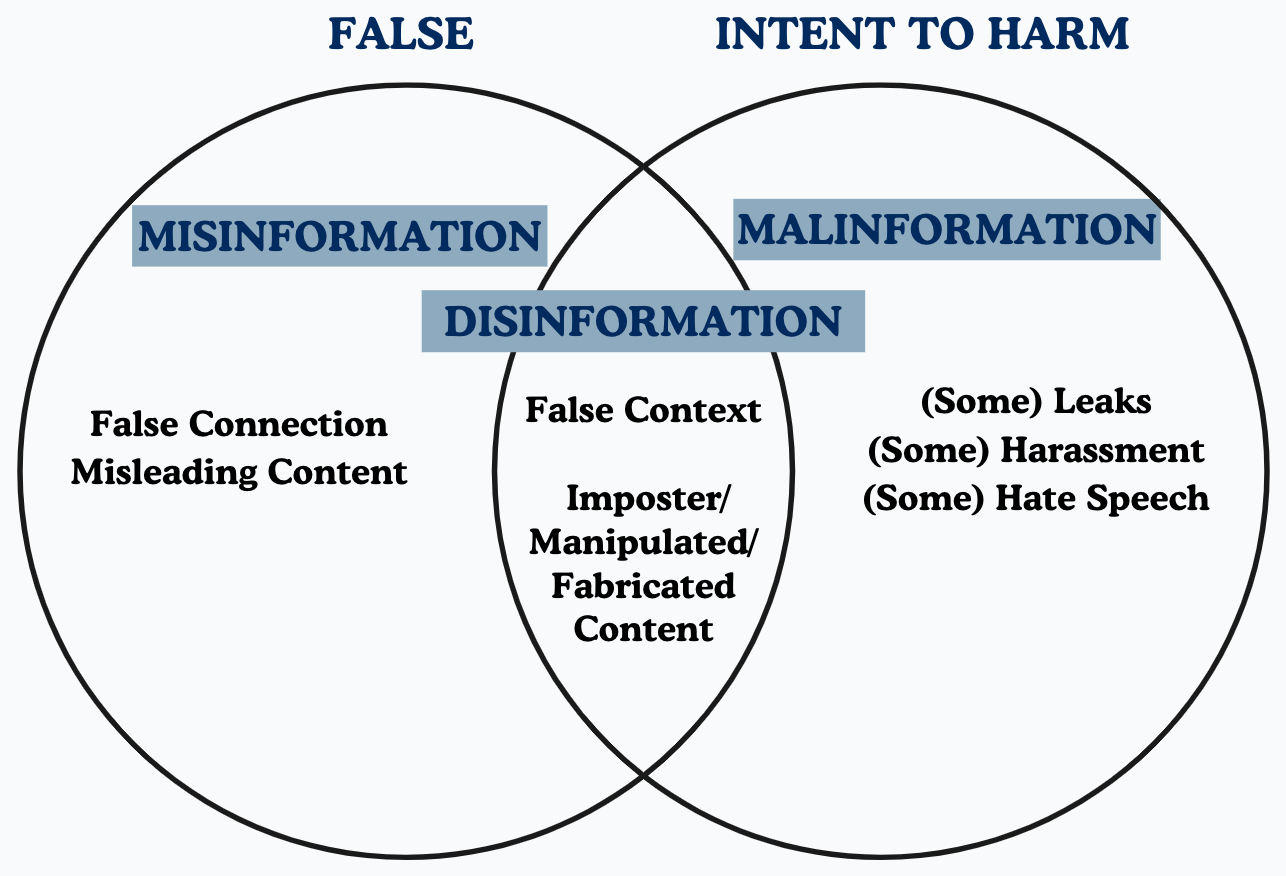

Information disorder, encompassing misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation, represents a significant challenge in the digital age (Kandel, 2020). The term refers to the spread of false or misleading information without regard for the outcome. Information disorder can take on various forms, including misleading content, fabricated stories, and manipulated images or videos (Pérez‐Escolar et al., 2023). These forms of information disorder can be disseminated through various channels, including social media platforms, where they can quickly reach a wide audience. Grade 1 of information disorder is characterized by a milder form, where individuals share false information without the explicit intent of causing harm (Pérez‐Escolar et al., 2023). Grade 2 is a more moderate level, as individuals develop and spread false information with the intention of gaining financial or political benefits, but not necessarily with the aim of causing harm; however, it could easily cause 'harm' indirectly or directly (Pérez‐Escolar et al., 2023). On the other hand, Grade 3 of information disorder represents a severe form, where individuals deliberately create and disseminate false information with the explicit intent of causing harm to others (Pérez‐Escolar et al., 2023).

The proliferation of information disorder, particularly on social media platforms, has become a pressing concern in contemporary society. While these platforms offer unprecedented connectivity and information access, they also provide fertile ground for the rapid dissemination of false information (Persily & Tucker, 2018). The decentralized and algorithm-driven nature of social media allows information disorder to spread quickly and widely, often without adequate oversight or moderation (Persily & Tucker, 2018). This spread of information has also created challenges, as malicious actors can exploit these platforms to spread false or misleading information. The viral nature of social media amplifies the reach of information disorder, making it difficult to contain onfce it has been disseminated (Pérez‐Escolar et al., 2023). One of the key factors contributing to the successful spread of information disorder on social media is the algorithmic design of these platforms (Pérez‐Escolar et al., 2023). Algorithms are designed to prioritize content that is likely to engage users with intense emotions, as highly motivating responses for engagement often lead to the amplification of sensational or controversial information.

The impact of MDM on democratic societies is profound. It can erode trust in institutions, polarize public discourse, and undermine democratic processes (Bannerman, 2020). Information disorder can be used to manipulate public opinion, sow division, and undermine the credibility of legitimate sources of information. In extreme cases, information disorder can incite violence or lead to harmful behaviors, highlighting the urgent need to address this issue (Pérez‐Escolar et al., 2023). By understanding the nature of the information disorder and its impact on democratic societies, policymakers and stakeholders can work towards developing effective strategies to mitigate its effects and promote a more informed and resilient public discourse.

Misinformation, as defined by Pérez‐Escolar et al. (2023), encompasses a wide range of false or inaccurate information that is disseminated, often unintentionally, to deceive or mislead individuals. This can include misleading content, which presents information in a way that distorts or misrepresents the truth, fabricated stories that are entirely false and created to deceive, and manipulated images or videos that are altered to convey a false narrative (Pérez‐Escolar et al., 2023). Misinformation may seem harmless on the surface, but it can still contribute to confusion and misunderstandings. While there may be no clear intent to harm, it can lead to incorrect beliefs or actions based on false information that can result in harm (Sawchuk, 2024). Disinformation is intentionally false and meant to cause harm. It can have serious consequences, such as influencing public opinion, destabilizing governments, or inciting violence (Sawchuk, 2024). Unlike misinformation, which may be spread inadvertently, disinformation is intentionally created and disseminated with the aim of misleading others (Cummings & Kong, 2019). This distinction is important because it highlights the malicious intent behind the creation and dissemination of disinformation, which is often used to manipulate public opinion or undermine trust in institutions. Malinformation refers to true information that is shared with the intent to harm a person, group, or organization (Cummings & Kong, 2019). This can include the unauthorized sharing of personal or private information, such as spreading rumors or releasing private correspondence, with the aim of damaging someone's reputation or causing harm (Sawchuk, 2024).

Adapted from Kandel, 2020

Distinguishing between misinformation, malinformation, and disinformation is crucial in understanding the intent and impact of false or misleading information and shaping responses to address these challenges effectively. Intent and impact are distinct, as a good intent can have a negative impact and vice versa. Each term reflects a different level of intent and harm associated with the spread of false information (Sawchuk, 2024). Misinformation implies inadvertent sharing of false information, while malinformation and disinformation suggest varying degrees of deliberate intent to harm or deceive (Linkov et al., 2019). This distinction via intent is essential in determining the appropriate legal and regulatory responses.

For instance, laws targeting disinformation might focus on deliberate attempts to deceive or manipulate, while laws addressing misinformation might emphasize promoting accuracy and transparency (Sawchuk, 2024). These laws could require platforms and individuals to take reasonable steps to verify the accuracy of the information they share, particularly if it has the potential to cause harm. For example, Singapore's Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) targets both misinformation and disinformation (Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, 2019). Under POFMA, individuals or entities found guilty of spreading false information can be fined or imprisoned (Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, 2019). The law also empowers government ministers to issue correction orders or take-down notices for false information (Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, 2019). This approach aims to attend to both deliberate and unintentional misinformation by holding individuals and platforms accountable for the accuracy of the information they share. Such a regulatory framework must be transparent, accountable, and subject to judicial oversight to prevent abuse.

Differentiating between these terms can inform the development of laws and regulations aimed at addressing harmful content online. The distinctions also play a significant role in determining platform responsibility. Platforms may be expected to take more aggressive action against disinformation, where there is a clear intent to deceive, compared to misinformation, which may be more about errors, misunderstandings, or a lack of knowledge. These distinctions can inform the development of policies and practices for content moderation and user engagement on digital platforms. Moreover, these distinctions can influence how legal action is pursued against individuals or entities spreading false information. Proving malicious intent may be required for certain legal actions related to disinformation or malinformation.

Internationally, varying definitions of these terms can complicate efforts to harmonize laws and regulations across borders. For example, a country that defines disinformation narrowly may have different legal standards for holding platforms accountable compared to a country with a broader definition. This can create challenges when addressing cross-border issues, such as the spread of harmful content across different jurisdictions. Differences in definitions can also influence how countries engage in international policy discussions and cooperation. Countries with stricter definitions of disinformation may advocate for more robust international agreements and enforcement mechanisms, while those with broader definitions may prioritize initiatives aimed at promoting media literacy and information sharing. Additionally, differing definitions can affect how international legal frameworks, such as those developed by the United Nations or the EU, are interpreted and implemented by member states. Countries may apply their own definitions of misinformation, malinformation, and disinformation when implementing international agreements, potentially leading to inconsistencies in enforcement and accountability.

Canadian Legal Frameworks

The Canadian legal framework provides a foundation for addressing information disorder, encompassing laws and regulations that aim to prevent harm caused by false or misleading information while respecting freedom of expression. One key aspect of this framework is the Criminal Code of Canada, which includes Section 181, introduced in 2003, prohibiting the spreading of false news with the intent to injure or alarm any person (Hamilton & Robinson, 2019). This provision targets information disorder intended to cause harm or panic, emphasizing the responsibility of individuals to disseminate accurate information (Havelin, 2021). Additionally, the Competition Act's Sections 52 and 74.01 address false or misleading advertising, encompassing misinformation that deceives the public (Havelin, 2021).

During elections, the Canada Elections Act's Section 91 prohibits making false statements about a candidate, including spreading misinformation (Hamilton & Robinson, 2019). This aimed to ensure the integrity of the electoral process by preventing the dissemination of false information that could influence voters. Moreover, the Broadcasting Act's Section 5(1)(b) mandates the Canadian broadcasting system to provide a reasonable opportunity for the public to be exposed to the expression of differing views on matters of public concern, relevant in confronting one-sided or misleading information (Hamilton & Robinson, 2019). This provision is relevant in facing one-sided or misleading information by promoting diverse perspectives. Furthermore, the Canadian Human Rights Act's Section 13 prohibits the communication of hate messages by telephone or on the internet (Havelin, 2021). While not directly targeting information disorder, this provision can encompass false information intended to promote hatred against an identifiable group, highlighting the broader societal impacts of information disorder. The Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) plays a crucial role in regulating the broadcasting and telecommunications sectors, ensuring that information disseminated through these media is accurate, reliable, and in the public interest. The CRTC sets standards for content, including news and information programming, to ensure that it is truthful and fair. Additionally, the CRTC oversees licensing and compliance for broadcasters and telecommunications providers, further strengthening its ability to regulate the dissemination of information (Havelin, 2021). However, the CRTC does not encompass social media.

However, these regulations must be considered in conjunction with constitutional principles, particularly freedom of expression, which is protected under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms outlines freedom of expression as a Fundamental Freedom and states under section 2(b) that “2. Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms: (b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion, and expression including freedom of the press and other media of communication” (Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, S2(b)). While freedom of expression is a fundamental right, it is not considered absolute in Canada. This constitutional protection of freedom of expression is fundamental to the functioning of a democratic society, as it allows for the free exchange of ideas and opinions.

The challenge of maintaining a middle ground between freedom of speech and the need to deal with information disorder is compounded by the prevalence of social media platforms. Social media platforms have revolutionized the way information is shared and consumed, enabling individuals to interact with a vast array of content and opinions, with these platforms becoming primary sources of information for many individuals (Goldzweig et al., 2018). However, the viral nature of social media can amplify the reach of information disorder, making it difficult to contain once it has been disseminated (Bannerman, 2020). This has led to calls for increased regulation of social media platforms to combat the spread of information disorder as well as some pushing for them to be recategorized as broadcasters (Bannerman, 2020).

In addressing information disorder, it is crucial to consider the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders, including governments, media platforms, and users, within the legal framework. Governments play a critical role in setting regulations and enforcing laws that govern the dissemination of information, ensuring that legal frameworks effectively address information disorder. Media platforms, as intermediaries, should also play a role in moderating content and preventing the spread of information disorder on their platforms through mechanisms such as fact-checking and content moderation. While not a current reality, users should also have a responsibility to critically evaluate information before sharing it and to report MDM when they encounter it. Understanding and fulfilling these roles and responsibilities are essential for ensuring the effectiveness of the legal framework in undertaking MDM.

Case Studies

In Canada, legal responses to information disorder have been shaped by a range of defamation and hate speech cases that have tested the boundaries of free speech and the responsibilities of individuals and media organizations. These cases highlight the complexities involved in regulating false information and protecting vulnerable communities from harm.

Grant v. Torstar Corp. [2009]

Grant v. Torstar Corp., 2009 SCC 61, is a landmark case that has reshaped Canadian defamation law, particularly in the context of freedom of expression, responsible journalism, and reputation protection. This case stands out for its profound impact on the legal landscape, providing clarity on the boundaries of defamation law and introducing the "responsible communication" defense. Prior to Grant v. Torstar Corp., defamation law in Canada primarily focused on protecting individuals' reputations from false and damaging statements. However, the case recognized the importance of balancing this protection with the fundamental right to freedom of expression, especially in matters of public interest (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). This recognition was crucial in acknowledging the role of the media and other communicators in facilitating public debate and democratic discourse. One of the key contributions of Grant v. Torstar Corp. was the introduction of the "responsible communication" defense (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). This defense allows for a more nuanced analysis of defamation cases, particularly those involving matters of public interest. It requires courts to consider whether the defendant acted responsibly in publishing the allegedly defamatory statements, taking into account factors such as the seriousness of the allegation, the public importance of the matter, the urgency of the communication, and the reliability of the source (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). By introducing this defense, the Supreme Court of Canada sought to encourage responsible journalism and robust public debate while still providing a remedy for individuals whose reputations have been unjustly harmed. The defense has since been recognized as a crucial tool in combating MDM and defamation, as it incentivizes journalists and publishers to verify information and report responsibly on matters of public interest.

The case of Grant v. Torstar Corp., 2009 SCC 61, originated from an article published by the Toronto Star concerning Peter Grant, a well-known businessman, and his endeavors to construct a golf course on ecologically delicate land (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). The article, written by Bill Schiller, a feature writer for the Toronto Star, highlighted Grant's significant financial contributions to the Conservative Party and various politicians (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). It suggested that Grant's financial support had garnered him favor with the government, particularly in his efforts to acquire crown land for the golf course project (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). The article also raised concerns from local residents and environmentalists about the potential environmental impact of the golf course development. Grant vehemently denied the implications of the article and argued that it had damaged his reputation and business interests. He filed a defamation suit against Torstar Corp., the publisher of the Toronto Star, seeking damages for libel. The case proceeded through the Canadian court system, with the Ontario Superior Court initially ruling in favor of Grant, finding that the article was defamatory (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). However, the Ontario Court of Appeal overturned this decision, holding that the article was protected by the defense of responsible journalism and the public interest. The case eventually reached the Supreme Court of Canada, where the central issue was whether the responsible communication defense should be recognized in Canadian defamation law. The Supreme Court, in a landmark decision, held that the defense should indeed be recognized, emphasizing the importance of freedom of expression in matters of public interest (Grant v. Torstar Corp.).

The responsible communication defense introduced in Grant v. Torstar Corp. has proven to be a significant and effective tool in combating misinformation and defamation in Canada. By incentivizing journalists and publishers to uphold high standards of journalism, this defense helps ensure that the public receives accurate and reliable information on matters of public interest. This is crucial in a digital age where misinformation can spread rapidly and have serious consequences. One of the key strengths of the responsible communication defense is its ability to serve as a safeguard against frivolous defamation claims. Without this defense, individuals or organizations could potentially silence legitimate reporting or criticism by threatening defamation suits, which could hinder the public's ability to access important information. While not tested in the same manner, requiring plaintiffs to demonstrate that the publication was not made responsibly, the defense helps protect the public interest in receiving diverse and robust media coverage.

In Grant v. Torstar Corp., the Supreme Court's references to statutes, regulations, and previous cases played a crucial role in shaping the outcome and broader implications of the decision. One of the key legal instruments cited was the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which enshrines the right to freedom of expression as a fundamental freedom. This citation underscored the Court's recognition of the importance of protecting this fundamental right in the context of defamation law. The Court also referenced previous defamation cases, such as Hill v. Church of Scientology of Toronto, which established important principles regarding the consideration of freedom of expression and the protection of reputation (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). In Hill, the Court emphasized the need to consider the broader context of a statement when assessing its defamatory nature, highlighting the importance of context in defamation law. By referencing this and other cases, the Court in Grant v. Torstar Corp. demonstrated a commitment to interpreting defamation law in a manner that upholds fundamental rights and values, including freedom of expression (Grant v. Torstar Corp.).

The outcome of Grant v. Torstar Corp. was a landmark decision that affirmed the importance of protecting freedom of expression, particularly in cases involving matters of public interest. The Supreme Court's ruling set a precedent for responsible journalism, emphasizing the need for accurate and fair reporting on issues that are of public concern. One of the key implications of the case is the establishment of a framework for courts to assess the responsibility of publishers when reporting on matters of public interest. This framework strikes a balance between protecting individual reputations and ensuring robust public discourse (Grant v. Torstar Corp.). It recognizes that journalists and publishers play a vital role in informing the public about matters of public interest, and that they should be able to do so without fear of frivolous defamation claims. At the same time, it holds them accountable for their reporting, ensuring that they act in a responsible and ethical manner.

R v. Keegstra [1990]

R. v. Keegstra was a landmark case in Canadian legal history that dealt with the issue of hate speech and its limits under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The case centered around James Keegstra, a high school teacher in Alberta who taught anti-Semitic views to his students, including denying the Holocaust and promoting conspiracy theories about Jewish control of world affairs (R v. Keegstra). Keegstra's teachings came to the attention of school authorities and eventually led to his dismissal. He was charged under section 319(2) of the Criminal Code, which prohibits the willful promotion of hatred against an identifiable group (R v. Keegstra). Keegstra was convicted at trial, but the Alberta Court of Appeal overturned the conviction, ruling that the law violated the right to freedom of expression under the Charter (R v. Keegstra). The case ultimately reached the Supreme Court of Canada, which heard arguments in 1989. In its landmark decision, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of section 319(2) of the Criminal Code, ruling that the law was a reasonable limit on freedom of expression under the Charter (R v. Keegstra). The Court held that the harm caused by hate speech justified the limitation on freedom of expression and that promoting hatred against an identifiable group was not a legitimate form of expression protected by the Charter (R v. Keegstra). The decision in R. v. Keegstra established an important precedent regarding the limits of freedom of expression in Canada. It confirmed that hate speech laws were a valid tool for addressing discrimination and promoting social harmony, even if they restricted certain forms of expression. The case highlighted the importance of balancing individual rights with the protection of vulnerable groups and set the stage for future cases involving hate speech and freedom of expression in Canada.

The outcome of R. v. Keegstra highlighted the judiciary's role in considering competing rights and interests. While recognizing the seriousness of the infringement on freedom of expression, the Court determined that the harm caused by hate propaganda justified the limitation imposed by section 319(2) (R v. Keegstra). This decision underscored the importance of safeguarding vulnerable communities from the harmful effects of misinformation and defamation. Moreover, the legal response in R. v. Keegstra emphasized the responsibility of educators and public figures in disseminating accurate information and fostering inclusive environments (R v. Keegstra). Fast forward to the present day, where the world is grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, two Ontario doctors, Dr. Patrick Phillips and Dr. Kulvinder Kaur Gill, have come under review for allegedly promoting misinformation about COVID-19 early in the pandemic (Loriggio, 2021) (Nicholson & Belllmare, 2020). While these cases are still in the process of being brought to provincial and federal court levels, R. v. Keegstra provides a precedent for the legal consideration of the responsibility of professionals in providing accurate information.

Notably, both Grant v. Torstar Corp and R.v. Keegstra cases predate the widespread use of social media platforms, which have since transformed the landscape of MDM dissemination. It is important to note that media and social media are not the same entities. Media is currently bound by legal frameworks applied to media companies, broadcasters, newspapers, and publishers, while social media does not fall under that same categorization as 'platforms', resulting in these regulations not applying to it. With the rise of social media, the spread of false information has become more rapid and widespread, posing new challenges for legal responses. Unlike traditional media outlets, social media platforms often operate on a global scale, making it difficult to apply traditional legal frameworks that are based on national jurisdiction. False information can be shared, liked, and commented on within seconds, reaching a wide audience before it can be effectively addressed. This rapid dissemination can amplify the harmful effects of information disorder, making it more challenging for legal systems to mitigate its impact. Moreover, the anonymity afforded by social media platforms can make it difficult to hold individuals accountable for spreading information disorder. Unlike traditional media outlets, where journalists and editors can be held responsible for false information, social media allows users to spread MDM without revealing their identity. This anonymity complicates legal responses, as identifying and prosecuting individuals who spread information disorder can be challenging. In light of these challenges, there is a growing recognition of the need to adapt legal responses to address the unique characteristics of social media.

The problem of not having any legal precedence in online information disorder in Canada is a significant challenge. While Canada has laws that prohibit hate speech, defamation, and other forms of harmful speech, these laws were not designed to specifically address the unique challenges posed by online information disorder. Without clear legal precedents, it can be difficult for law enforcement agencies and courts to determine when online information disorder crosses the line into illegal speech. This ambiguity can create a chilling effect on legitimate speech and hinder efforts to undertake MDM effectively. Furthermore, the transnational nature of the internet presents challenges in enforcing Canadian laws against online MDM. Much of the content consumed by Canadians is hosted on servers located outside of the country, making it difficult to hold foreign entities accountable under Canadian law. To address these challenges, there is a need for comprehensive legal frameworks that specifically address online information disorder. This could include laws that require online platforms to take proactive measures to address the information disorder, such as fact-checking and labeling false information. It could also involve mechanisms for swift and effective enforcement against individuals and entities that spread information disorder online.

International Perspectives

There is a wide array of policy responses and solutions to information disorder globally. However, these measures are often implemented at a national level, with limited coordination or collaboration between countries (Post & Maduro, 2020). This lack of international synthesis on effective strategies for tackling information disorder makes it challenging for policymakers to make informed decisions based on the experiences of other nations. As a result, countries have repeatedly tried similar approaches to addressing information disorder in recent years, but these efforts have met with limited success (Post & Maduro, 2020). There is a need for greater international cooperation and knowledge-sharing to develop more effective and coordinated strategies for addressing information disorder globally.

However, two significant pieces of international legislation, the Digital Services Act (DSA) in the EU, introduced in 2024, and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act in the United States, introduced in 1996, represent significant pieces of international legislation that offer different approaches to addressing the responsibilities of online platforms regarding user-generated content.

The DSA, as outlined in its objective, aims to establish a harmonized legal framework for digital services, including online platforms, to ensure their accountability and a safer online environment. It introduces the concept of "gatekeeper platforms" that are subject to stricter obligations and liability for illegal content and activities on their platforms (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, 2022). Non-gatekeeper platforms also have responsibilities to address illegal content, but with more limited liability (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, 2022). On the other hand, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act in the US provides broad immunity to online platforms from liability for content posted by their users, as when the act was written, user-generated content was less prominent. This immunity allows platforms to moderate content without being treated as publishers, thereby fostering innovation and growth in the internet sector in the US (47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1)).

One key difference between the two approaches is their treatment of liability. The DSA imposes stricter obligations and liability on platforms, especially gatekeepers, for illegal content on their platforms, suggesting the DSA is rights-based (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, 2022). In contrast, Section 230 shields platforms from liability, enabling them to moderate content without facing legal repercussions. Another difference lies in their enforcement mechanisms (47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1)). The DSA proposes significant fines for non-compliance, with measures for supervision and oversight (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, 2022). In contrast, the protections afforded by Section 230 are primarily through legal challenges and court rulings, with platforms being held accountable for moderation decisions if deemed to be acting in bad faith (47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1)). Furthermore, Section 230 applies to US companies domestically, whereas the DSA applies to all digital companies with services in the EU. Critics of the DSA argue that its stringent requirements, particularly for gatekeeper platforms, could stifle innovation and hinder the growth of digital services in the EU. In contrast, Section 230 has been credited with fostering innovation and the growth of the internet in the US by providing a legal framework that encourages platforms to host user-generated content without the fear of legal liability. Arguably, the rigorous requirements of the DSA respond to the failure of Section 230 to protect the rights of users. The DSA and Section 230 represent different approaches to addressing the responsibilities of online platforms regarding user-generated content. While the DSA aims to establish a harmonized legal framework with stricter obligations and liability, Section 230 provides broad immunity to platforms, fostering innovation and growth in the internet sector (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, 2022) (47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1)). Understanding these contrasting approaches can provide insights into the strengths and weaknesses of different regulatory models and inform discussions on international cooperation and knowledge-sharing in addressing information disorder on a global scale.

Neither the DSA nor Section 230 uses the term "information disorder" specifically. However, both pieces of legislation address issues related to content moderation and the responsibilities of online platforms regarding the content posted by their users, which are often associated with the broader concept of information disorder, including misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation. They both play a significant role in shaping the regulatory environment, or lack of regulatory environment, for online platforms and their approach to content moderation. By establishing legal frameworks that define the responsibilities of online platforms regarding content posted by users, these laws aim to mitigate the harmful effects of misinformation and other forms of information disorder online.

Regulatory Challenges

Regulating information disorder online presents complex challenges that necessitate holistic solutions. A key challenge stems from the sheer volume of information available on the internet and the speed at which it can be disseminated. The decentralized, extranational nature of online platforms, coupled with the anonymity they afford users, further complicates efforts to track and identify the sources of MDM. Additionally, algorithms that prioritize meaningful, engaging content can inadvertently contribute to the spread of information disorder by amplifying sensational or provocative material. Jurisdictional issues compound the challenge of regulating MDM online, as the internet transcends national borders. Unlike traditional media, online platforms often operate across multiple jurisdictions and may be subject to different legal standards. This makes it difficult for regulators to enforce compliance with MDM regulations and hold platforms accountable for the spread of false information. A social media platform based in one country may be subject to different legal standards than a similar platform based in another country. However, it is important to note that most social media platforms are based in the US. This disparity in legal standards can create challenges in determining which jurisdiction's laws apply and how they should be enforced. These challenges are exacerbated by differences in legal standards and enforcement mechanisms between jurisdictions, creating gaps that allow information disorder to proliferate in areas with weaker regulations.

For instance, misinformation originating in countries with lax regulations can evade accountability in nations with stricter laws, underscoring the need for regulatory equivalency rather than just international cooperation. A pertinent example is the spread of misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic. In early 2020, conspiracy theories such as the "lab leak" theory, which falsely suggested that the virus was artificially created and intentionally released, circulated widely online. This misinformation, initially gaining traction in the United States, spread globally, including to countries like China, where it was amplified by state media despite stringent information controls (Savoia et al., 2022). This situation demonstrates that while international cooperation is important, effective regulation also requires equivalent standards across countries. If individual nations adopted proactive regulatory frameworks similar to the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA), which mandates companies to self-regulate and address misinformation proactively, rather than reactively responding to challenges, the impact of cross-border misinformation could be significantly mitigated.

Ethical considerations and trade-offs play a crucial role in the regulation of speech in the digital realm, especially concerning misinformation. While tackling misinformation is essential to protect the public from its harmful effects, regulatory efforts must also respect the fundamental right to freedom of expression and the open exchange of ideas. This balancing act requires careful consideration of the potential impacts of regulatory measures on freedom of speech, as well as the potential for unintended consequences such as censorship or the stifling of legitimate debate. A key ethical consideration in regulating misinformation is the potential for overreach and censorship. The line between misinformation and legitimate speech can be blurry, and efforts to regulate misinformation must be careful not to inadvertently suppress valid opinions or alternative viewpoints. Additionally, the use of automated content moderation tools to identify and remove misinformation can raise concerns about the fairness and accuracy of such tools, as well as the potential for bias or error. Another ethical consideration is the impact of regulatory measures on freedom of expression.

While seeing to MDM is important, regulatory efforts must consider both protecting the public from harmful information and allowing for the free flow of ideas and information. Overly restrictive regulations can infringe on individuals' right to freedom of expression and limit their ability to access information and engage in public discourse. Moreover, there is a trade-off between the effectiveness of regulatory measures and their impact on freedom of expression. Stricter regulations may be more effective in combating information disorder, but could also have a negative effect on free speech. Conversely, less restrictive regulations may preserve freedom of expression but may be less effective in addressing the spread of information disorder. Addressing these ethical considerations requires a multifaceted approach that takes into account the unique nature of the digital environment.

Policy Responses and Solutions

Fact-checking initiatives are integral to combating the proliferation of MDM online, providing a crucial line of defense against the spread of false or misleading information. Organizations such as FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, and Snopes play a vital role in this effort, employing teams of researchers and journalists to independently verify the accuracy of claims circulating in the media and on social platforms. These fact-checkers rigorously assess the credibility of sources, cross-reference information with reliable data, and consult experts to ensure the accuracy of their findings. One notable example of the impact of fact-checking initiatives is their role during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the virus spread rapidly around the world, so too did misinformation and false claims about the virus and potential treatments. Fact-checkers played a crucial role in debunking these falsehoods, providing the public with accurate information and helping to prevent the spread of MDM. Through the International Fact-Checking Network, fact-checkers from around the world collaborated to verify claims related to COVID-19, ensuring that accurate information was disseminated to the public (International Fact-Checking Network, n.d.). The effectiveness of fact-checking initiatives lies in their ability to provide the public with reliable, evidence-based information. By debunking false claims and providing accurate information, fact-checkers help to build trust in the media and promote informed decision-making. However, despite their effectiveness, fact-checking initiatives face challenges, including the sheer volume of information disorder online, the speed at which false information can spread, and the challenge of reaching audiences who may be predisposed to believe false claims.

Media literacy programs play a crucial role in equipping individuals with the skills to navigate the complexities of the digital information landscape. For instance, the MediaWise initiative in the United States has been instrumental in providing media literacy training to young people (MediaWise, n.d.). Through workshops, educational materials, and online resources, MediaWise teaches participants how to critically evaluate information online, identify MDM, and differentiate between reliable and unreliable sources (MediaWise, n.d.). By empowering young people with these skills, MediaWise aims to cultivate a generation of informed and discerning consumers of information who can confidently navigate the digital world. Similarly, the European Commission has taken steps to promote media literacy across Europe through initiatives such as the European Media Literacy Week (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017). This initiative seeks to raise awareness about the importance of media literacy and provide individuals with the tools they need to critically engage with media and information. By funding projects that promote media literacy, the European Commission aims to empower citizens to become active participants in the digital information landscape, capable of critically evaluating information and making informed decisions (Chan, 2023). By teaching individuals how to critically evaluate information, media literacy programs not only help to reduce the spread of information disorder but also empower individuals to become more engaged and informed citizens. However, with increasingly sophisticated fake content, it's unrealistic to expect individuals, especially those without technical expertise, to accurately MDM. While skepticism is important, placing the responsibility on the public to detect MDM is unfair and ineffective. The burden should lie with platforms and authorities to implement robust detection and verification systems, ensuring the public isn’t solely responsible for navigating complex digital misinformation. As the digital information landscape continues to evolve, media literacy programs will play an increasingly important role in fostering a more informed, resilient, and democratic society.

Regulatory frameworks are often seen as a necessary tool in addressing the information disorder, particularly in the era of digitalization, where information spreads rapidly across borders. For instance, the French law, loi n° 2018-1202, Law Against the Manipulation of Information, mandates that online platform operators create mechanisms for users to report false information that could disrupt public order or distort the accuracy of the vote (Jang et al., 2019). Platforms must review and act on these reports within 48 hours, either removing or flagging misleading content, with a focus on protecting electoral integrity. The law also mandates transparency, requiring platforms to report back to the government on their actions. While these regulations are intended to uphold the integrity of information shared online, they have sparked debates about the potential for censorship and the limitation of freedom of expression. The internet transcends national boundaries, making it challenging to ensure that all online platforms comply with the same set of rules. This issue is further complicated by varying cultural and legal norms, as what constitutes MDM or harmful content may differ from one country to another. Moreover, the effectiveness of regulatory frameworks in tackling MDM is often questioned. Critics argue that such regulations may lead to overreach by governments and restrict legitimate forms of expression. Despite these challenges, regulatory frameworks can still play a vital role in addressing MDM. By establishing clear guidelines and accountability mechanisms for online platforms, these regulations can encourage greater transparency and responsibility in the dissemination of information. However, striking the right balance between regulation and freedom of expression remains a complex and ongoing challenge for policymakers around the world.

In Australia, the government has taken proactive steps to address MDM through legislative measures, recognizing the increasing influence of online platforms on public discourse. A significant focus of the Australian government's efforts has been to increase transparency around online advertising, particularly political advertising, which has been a notable channel for the spread of misinformation during elections. Legislation mandates that digital platforms must clearly label political advertisements and disclose key details such as who paid for the advertisement, how much was spent, and the specific demographic or geographic targeting employed. These measures ensure that voters can trace the origins of the advertisements they encounter, making it easier to identify potentially misleading content and understand the interests driving it (Chen et al., 2023). In addition to regulatory oversight, Australia has made media literacy a central component of its MDM strategy. The government recognizes that equipping individuals with critical thinking skills is essential for combating the effects of misinformation (Chen et al., 2023). By implementing these measures, the Australian government aims to create a more transparent and accountable online environment that is resilient to information disorder.

Future Trends and Directions

In the realm of emerging challenges, the evolution of information disorder is intertwined with advancements in technology. Deepfake technology, for instance, allows for the creation of highly convincing fake audio and video content, making it increasingly difficult to discern truth from falsehood. As this technology becomes more accessible and sophisticated, it poses a significant threat to public trust and the integrity of information online. Deepfakes can be used to create realistic-looking videos of public figures saying or doing things they never actually did, leading to the manipulation of public opinion. The proliferation of deep fake technology presents an increasingly credible risk to the integrity of democratic processes and the administration of justice. On election day, for instance, the dissemination of a fabricated video falsely portraying the death of a political candidate could materially distort public perception and interfere with the free and fair functioning of the electoral process. Similarly, the introduction of deep fake-generated evidence into judicial proceedings may undermine evidentiary standards, erode public confidence in the legal system, and compromise the principle of due process. These risks warrant urgent consideration within regulatory and legal frameworks governing information integrity, electoral conduct, and evidentiary admissibility. Deepfake technology can be used to create fake news stories that are designed to deceive and manipulate audiences. The rise of deep fakes highlights the need for robust legal responses to combat the spread of false information online. Existing laws may need to be updated to address the unique challenges posed by deepfake technology, such as the creation and dissemination of fake audio and video content. Additionally, efforts to educate the public about deep fakes and how to identify them are crucial in mitigating their impact on public trust and the integrity of information online.

To address these challenges, future legal responses and regulatory strategies must adapt to the evolving nature of the information disorder. One potential approach is to introduce regulations that require social media platforms to implement transparency measures regarding the origin and veracity of content. This could involve labeling or flagging disputed information, as well as providing users with more control over the content they are exposed to, or even the opposite, where real content is subject to verification stamping. Another strategy could involve enhancing the accountability of platforms for the content they host. This could be achieved through legislation that holds platforms liable for the spread of false information, similar to the legal frameworks governing traditional media outlets.

Furthermore, continued research and policy development are essential to effectively address information disorder. This includes further exploration of the psychology of the information disorder, the development of new technologies to detect and address false information, and the evaluation of the effectiveness of different regulatory approaches. By fostering collaboration between researchers, policymakers, and technology companies, we can develop holistic strategies to address information disorder and promote a more informed public discourse.

Conclusion

By 1972, 4 years after the founding of the CRTC, the television broadcasting regulator in Canada, around 75% of Canadians had access to daily television (Williams, 2001). In 2024, 81.9% of Canadians use social media daily (Kemp, 2024). Despite this widespread use, there has been a notable absence of significant legislation regulating social media content in Canada, reflecting a similar situation in the US. The rapid proliferation of social media platforms and their integration into everyday life have fundamentally altered the way information is disseminated and consumed. Unlike traditional media outlets, social media platforms operate in a largely unregulated environment, allowing the information disorder to spread rapidly and unchecked, with the current patchwork of legislation failing to regulate it effectively.

The phenomenon of information disorder poses significant challenges in the digital age, requiring comprehensive and multifaceted responses from policymakers, researchers, and society as a whole. Legal frameworks, such as the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Digital Services Act in the EU, play a crucial role in defining the responsibilities of online platforms regarding user-generated content. The lack of coordination between countries often results in duplicated efforts and limited success in addressing information disorder. By sharing experiences and regulatory frameworks from different jurisdictions, countries can learn from one another and develop more effective, coordinated strategies to address information disorder on a global scale. Combating the information disorder requires a holistic and collaborative approach that balances the protection of fundamental rights with the need to address the harmful effects of false information. By implementing comprehensive legal frameworks, promoting international cooperation, and investing in fact-checking and media literacy programs, we can build a more resilient and informed society capable of navigating the complexities of the digital information age

References

47 U.S. Code § 230 - Protection for Private Blocking and Screening of Offensive Material, 47 230. Retrieved March 16, 2024, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230

Bannerman, S. (2020). Canadian Communication Policy and Law. Canadian Scholars. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utoronto/detail.action?docID=6282022

Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. (2022, February 23). How to identify misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (ITSAP.00.300). Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. https://www.cyber.gc.ca/en/guidance/how-identify-misinformation-disinformation-and-malinformation-itsap00300

Chan, E. (2023). Analysis of the Challenge in Fake News and Misinformation Regulation Comparative in Global Media Landscape. SHS Web of Conferences, 178, 02018. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202317802018

Chen, S., Xiao, L., & Kumar, A. (2023). Spread of misinformation on social media: What contributes to it and how to combat it. Computers in Human Behavior, 141, 107643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107643

Cummings, C., & Kong, W. Y. (2019). Breaking down “fake news”: Differences between misinformation, disinformation, rumors, and propaganda. In Resilience and Hybrid Threats: Security and Integrity for the Digital World. IOS Press.

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. (n.d.). Foreign Influence Operations and Disinformation | Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency CISA. Retrieved March 16, 2024, from https://www.cisa.gov/topics/election-security/foreign-influence-operations-and-disinformation

European Commission. (2020, December 3). *Communication From The Commission To The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic And Social Committee And The Committee Of The Regions On The European Democracy Action Plan. European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0790

Goldzweig, R., Wachinger, M., Stockmann, D., & Römmele, A. (2018). Beyond Regulation: Approaching the challenges of the new media environment. LSE IDEAS. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep45251

Grant v. Torstar Corp. [2009] 3 SCR 640, [2009] 3 SCR 640 ___ (Supreme Court of Canada 2009). https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/7837/index.do

Hamilton, S., & Robinson, S. (2019). Law’s Expression – Communication, Law and Media in Canada, 2nd Edition | LexisNexis Canada. https://store.lexisnexis.ca/en/products/laws-expression-communication-law-and-media-in-canada-2nd-edition-lexisnexis-canada-skusku-cad-00789/details

Havelin, M. (2021). Misinformation & Disinformation in Canadian Society. A system analysis & futures study [MRP]. OCAD University. https://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/3505/1/Havelin_Miriam_2021_MDes_SFI_MRP.pdf

International Fact-Checking Network. (n.d.). Poynter. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.poynter.org/ifcn/

Jang, S. M., Mckeever, B. W., Mckeever, R., & Kim, J. K. (2019). From Social Media to Mainstream News: The Information Flow of the Vaccine-Autism Controversy in the US, Canada, and the UK. Health Communication, 34(1), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1384433

Kandel, N. (2020). Information Disorder Syndrome and its Management. JNMA: Journal of the Nepal Medical Association, 58(224), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.31729/jnma.4968

Kemp, S. (2024, February 22). Digital 2024: Canada. DataReportal – Global Digital Insights. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-canada

Linkov, I., Roslycky, L., & Trump, B. D. (2019). Resilience and Hybrid Threats: Security and Integrity for the Digital World. IOS Press.

Loriggio, P. (2021). Ontario’s medical regulator imposes restrictions on doctor accused of spreading COVID misinformation. The Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/ontario-s-medical-regulator-imposes-restrictions-on-doctor-accused-of-spreading-covid-misinformation/article_183ad64a-c2e6-5f9b-b79c-fcd99ef0bd63.html

MediaWise. (n.d.). Poynter. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.poynter.org/mediawise/

Nicholson, K., & Bellemare, A. (2020, August 10). Ontario doctor subject of complaints after COVID-19 tweets. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/kulvinder-kaur-gill-tweets-cpso-1.5680122

Pérez-Escolar, M., Lilleker, D., & Tapia-Frade, A. (2023). A Systematic Literature Review of the Phenomenon of Disinformation and Misinformation. Media and Communication, 11. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6453

Persily, N., Tucker, J. A., & Tucker, J. A. (2020). Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform. Cambridge University Press.

Post, R., & Maduro, M. (2020). Misinformation and Technology: Rights and Regulation Across Borders (SSRN Scholarly Paper 3732537). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3732537

Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019 - Singapore Statutes Online. Retrieved April 7, 2024, from https://sso.agc.gov.sg:5443/Act/POFMA2019?TransactionDate=20191001235959

R. v. Keegstram [1990] 3 SCR 697, 21118 (Supreme Court of Canada December 13, 1990). https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/695/index.do

Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 October 2022 on a Single Market For Digital Services and Amending Directive 2000/31/EC (Digital Services Act) (Text with EEA Relevance), 277 OJ L (2022). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/2065/oj/eng

Savoia, E., Harriman, N. W., Piltch-Loeb, R., Bonetti, M., Toffolutti, V., & Testa, M. A. (2022). Exploring the Association between Misinformation Endorsement, Opinions on the Government Response, Risk Perception, and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the US, Canada, and Italy. Vaccines (Basel), 10(5), 671-. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050671

Sawchuk, N. (2024). Research Guides: Research Essentials: Misinformation, Disinformation, and Malinformation. https://guides.iona.edu/researchessentials/disinformation

United Nations Development Programme. (2024). Rise Above: Countering misinformation and disinformation in the crisis setting. UNDP. https://www.undp.org/eurasia/dis/misinformation

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe Publishing. https://edoc.coe.int/en/media/7495-information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-research-and-policy-making.html

Williams, C. (2001). The evolution of communication—ARCHIVED. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-008-x/2000004/article/5559-eng.pdf

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.svg)

.svg)