2. Introduction

Despite rising globalization in the 21st century, the global economy is witnessing a rapid hike in protectionist policies that threaten the stability of international trade and cooperation. These policies are characterized by increased trade restrictions including import quotas, tariffs, and other government control measures. These moves are expected to benefit the countries imposing them in the short-run, but in the long-run, these will only lead to increased trade tensions and uncertainties. The increased advent of protectionism in recent years can be attributed to increased economic nationalism, national security concerns, encouragement to home-based industries and a backlash against globalization.

The US-China trade war, Atmanirbhar Bharat and the European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are manifestations of the diversification of reasons as well as results of protectionism on international trade, investment and economic growth. A review of these cases shows how differing economies respond under environmental, economic, and political pressures. The US-China trade war began in 2018 under the Trump administration and led to the imposition of tariffs on the import of Chinese goods to the US; this was justified through long-standing unfair trade practices and intellectual property theft. This has heightened tensions and led to retaliatory practices from China (Siripurapu and Berman, 2024). India’s Atmanirbhar Bharat initiative of 2020 began in the aftermath of Covid-19, to make India self-reliant in various sectors. India is looking to develop its resilience and employment generation capabilities as well (India.gov.in, 2021). The EU's CBAM is an innovative way to address deteriorating climatic conditions with a trade-related policy. Extra taxes and custom duties are being levied on carbon-intensive products imported from outside the EU where carbon emission can be controlled but the goals of the climate policy of the EU cannot be hindered. However, there are criticisms about its transparency and impact on developing economies (European Commission, 2024).

In the sections that follow, the paper examines each of these three cases individually to analyze the underlying motivations for protectionist policies and their diverse consequences on trade, growth and investment. By comparing these scenarios, the analysis aims to identify common patterns and divergences, ultimately offering recommendations for balancing domestic priorities with international cooperation. The urgency of the situation calls for building more resilient, sustainable, and inclusive global trade systems at the earliest.

3. Literature Review

This literature review focuses on the various factors that lead to the initiation of protectionist measures, along with other studies that examine the implications of these measures.

3.1. Reasons Behind Protectionism

According to certain studies, trade restrictions are usually driven by the desire to protect and promote domestic industries, particularly those in their early stages of development. These infant industries usually lack economies of scale and need greater support (Sun, 2024). Additionally, Giordani and Mariana, 2020 argue that higher levels of education can also lead to greater protectionism as unskilled workers form coalitions to protect their incomes, emphasizing the socio-economic aspect that often drives protectionism.

3.2. Empirical Studies

Empirical research on the US-China trade war reveals that the return of tariffs and quotas has caused a significant fall in the imports and exports from US and harmed workers engaged primarily in trade (Fajgelbaum et al., 2020). A study by Zhang, 2024, explains how this trade war can benefit certain countries in the short-run, but in the long-run, it will disrupt global trade and lead to reshoring.

The protectionist policies imposed by the EU are also on the rise. However, there are allegations of discriminatory imposition, as explained by N. Stanojević, 2021, who says that the trade tariffs by the EU have certain discriminatory characteristics, some of which are justified in emergency situations. While rising protectionism can have negative economic impacts in the Euro area, the escalating trade tensions are expected to influence the entire global economy negatively(Vanessa Gunnella et al., 2019).

3.3. Impact of Protectionist Measures

Some studies describe protectionism as a supply shock. According to these, it leads to a fall in output and a rise in inflation in the short-run, while the impact on the trade balance is only minimal (Barattieri, Cacciatore and Ghironi, 2021). According to a different research that focussed on the long-run impact in particular, the GDP and international trade experience a significant negative impact and persistent challenges with regard to economic growth (Gregori, 2021). ‘The Risk of Protectionism: What Can Be Lost?’ explains that protectionism threatens global economic development and growth, potentially harming economic growth, poverty alleviation measures, and reduction in inequalities (Marek Dabrowski, 2024).

4. Reasons Behind Rising Protectionism

A multitude of factors drives protectionist policies, and they demonstrate how a country chooses to respond to social, economic and political pressures.

4.1. Economic Nationalism

Economic nationalization talks about the importance of safeguarding domestic industries from foreign firms in the face of globalization. The approach aims at preserving jobs, boosting the home economy and fostering pride in home-grown products. According to the Vicepresidentofindia.nic.in, 2024, “Economic Nationalism is quintessentially fundamental to our economic growth; import only what is unavoidably essential” and focus on ‘Vocal for Local’; these are crucial examples of economic nationalism in the context of India. In recent years the EU has implemented these protectionist measures to promote fair trade and anti-dumping practices, therefore protecting European businesses from potential damage (Trendsresearch.org, 2024). As global competition becomes even more intense, the re-emergence of economic nationalisation raises questions about the long-term sustainability and efficiency of such an approach.

4.2. National Security

Another strong force driving protectionism is national security. To safeguard sovereignty and strategic sectors within the country, the states may adopt a set of trade restrictions; during this period of taut world politics, the practice has been quite common. Adam Smith, in the Wealth of Nations, wrote that exceptions to free trade could be permissible "when some particular sort of industry is necessary for the defence of the country."

The Trump administration in 2017-18 utilized Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, and started reducing imports and the FDI from China. This was supposed to reduce the Chinese control on business and economy in the US, thus ensuring national security (Cato.org, 2022). However, such actions also raise concerns about escalation, retaliation, and long-term disruption in existing and emerging trade partnerships.

4.3. Pushback Against Globalization

Globalization integrates the economy of each nation with a world economy. While it increases efficiency, trade and alternatives to consumers, it also makes the smaller producers worse off and increases inequalities. Protectionist measures aim to reduce these inequalities both in terms of income and opportunities, while preventing marginalization of communities. The WTO protests in Seattle, 1999, brought attention to the down-sides of globalization, with protestors voicing their concerns about workers’ rights, sustainability, environment and other social issues (Frantilla, 2019). Movements like these have forced people to look at globalization in a more critical light. This has led to a rethinking of liberal trade models and an increased acceptance of selective protectionism as a corrective and protective tool.

In conclusion, protectionism is driven by multifaceted factors to respond to changes that might occur within and outside the countries as well. Understanding these factors is crucial to understanding the impact of these measures on international trade, investment, and economic growth. Without addressing the root causes behind protectionism, global trade risks becoming increasingly fragmented, making coordinated responses even more difficult.

5. Case Studies

Three case studies are analyzed to examine the impact of protectionism across different scenarios. These highlight how changing relations between countries impact their economic growth, trade and investment journeys.

5.1. The US-China Trade War

The US-China trade war is a notable example of protectionist policies and their consequences. The tensions between the two trade giants began in 2018 under the Trump administration. In 2018, the US and China were significant trade partners with the value amounting to 658.79 billion USD. However, differences arose as the imports to the US far exceeded the exports from it; the imports to the US amounted to 538.51 billion USD while the exports were barely 20.28 billion USD. This trade imbalance was driven by steel and aluminum imports to the US (Statista, 2024). Along with this, the US was also concerned about theft of intellectual property rights, the situation of the domestic industries and the unfair advantage the Chinese producers had due to huge subsidization. National security too played a role, as the dependence on Chinese money and goods was very high (Kapustina et al., 2020).

The US imposed 25% tariffs on around 34 billion USD worth of imports including vehicles, aircraft components and others. China retaliated by imposing similar tariffs on 545 goods from the United States (Mullen, 2022). Due to this tariffs from both ends have escalated leading to disruptions in the supply chains (Khitakhunov, 2020).

The trade war had a significant impact on both the countries, value chains changed globally and trading partners saw a shift. The US now imports more from Mexico, Vietnam, and Taiwan, while China exports to other countries instead of the US. The issue that the US faced was the loss of citizens’ welfare due to more expensive products and limited choices especially in agricultural products, while China faced a loss in the total value of exports and saw an impact on its GDP (World Bank Open Data, 2015). Globally, this trade war led to increased market uncertainty, vulnerable supply chains and caused countries to rethink their strategy with China and the US (Daniel Parsapour, 2024). There was also a trend of reshoring as countries began to diversify their supply chains. Along with this, there were fluctuations in the stock market and investment levels due to the geopolitical uncertainty (Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal, 2021).

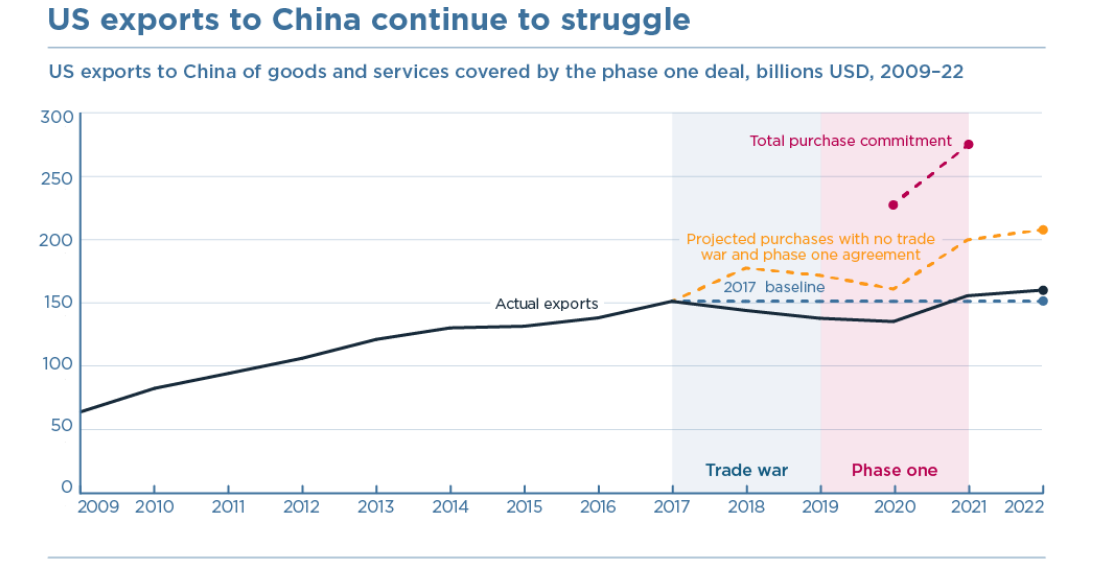

In 2020, a truce was signed between the two, called the Phase One Agreement, where China pledged to increase its imports from the US by 200 USD in two years. However, this target wasn’t reached and this escalated the animosity further (Bown and Wang, 2023).

Source: Peterson Institute for International Economics

Following this, the trade war came into picture once again in 2024, when the US imposed tariffs on the import of electric vehicles from China. This was done as China is the highest producer of EVs in the world, and the producers have high efficiency and extremely subsidized production facilities, which the US believes puts it at a disadvantage.

The US-China trade war demonstrates how trade tensions can escalate and damage bilateral relations while harming the economies in terms of their GDP, investment and trade.

5.2. India’s Atmanirbhar Bharat

A 2020 report by Acuite Ratings and Research identified 40 sub-sectors that contributed to imports of US$ 33.6 billion from China. This was while India possessed the capacity to replace 25% of Chinese imports without any additional imports. Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan or Self-Reliant India Mission was launched in May 2020 amidst the pandemic in a bid to strengthen India’s production capacity and make it self-reliant. Rs. 20 lakh crore corpus was announced by the government to promote domestic production across sectors and develop India into a global supply chain hub (India Brand Equity Foundation, n.d.).

One of the key schemes introduced under Aatmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan was the production-linked incentive scheme (PLI) that was allocated US$ 27.02 billion for five years from 2021-22. In addition, US$ 5.45 billion was set aside for PLI electronics manufacturing schemes. This has attracted foreign investment, with Amazon announcing a manufacturing plant in Chennai, and Apple starting iPhone 12 assembly in the first quarter of 2021.

Self-reliance in defense is a major goal of Aatmanirbhar Bharat. The government increased the FDI limit in defense manufacturing to 74% and introduced an import embargo on 101 defense items. The Defense Production and Export Promotion Policy 2020 envisions a US$ 25 billion turnover including US$ 5 billion exports in the aerospace and defense sectors by 2025. India’s arms imports have declined by 11% between 2013-17 and 2018-22 while defense exports increased tenfold between 2016-17 and 2022-23 to hit Rs.16,000 crores (Economic Times Online, 2023).

Atmanirbhar Bharat was the most successful on two fronts. On one hand the various stimulus packages helped revive the MSME sector that was adversely affected by the pandemic. On the other, greater self-reliance in the defence sector would help India to be less dependent on allies like the US or Russia for security needs. This in turn helps the country take an independent stance amidst tumultuous geopolitical scenarios and aids in its path to be world leader. But the policy is not without shortcomings. India must tread carefully so that self-reliance does not translate to domestic protectionism that fails to uphold quality standards. That would be detrimental to the very goals of Atmanirbhar Bharat and could potentially lead to an economic crisis similar to the one in 1990.

5.3. European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

The European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) was introduced as part of the European Green Deal to tackle the shortcomings of the EU Emission Trading System. The EU CBAM charges the embedded carbon in imported goods, thus equalizing the carbon price of domestic and imported goods and leveling the playing field (European Commission ,2024).

Five emission-intensive trade exposed (EITE) industries are covered by CBAM, namely cement, fertilizers, iron and steel, aluminum, and electricity. The impact of CBAM on trade is determined not only by the volume of exports to the EU but also by the share of CBA exports among total exports and the carbon-intensity of production. While Russia, China, UK, Turkiye, and Ukraine make up nearly 50% of CBA exports by volume, the countries most affected by the tariff are low-income countries (LICs) in Africa like Mozambique and Zimbabwe and LDCs and developing countries in Europe such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ukraine, Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Moldova, and Albania due to the dependence on CBA exports to EU (Carnegieendowment.org, 2023).

2021 research by UNCTAD found that increasing carbon prices in the EU would boost trade for developing nations in the absence of CBAM. However,the introduction of CBAM decreases the exports of developing countries and increases that of developed countries as they are at a better position to bear the cost of switching to clean energy. Intra-EU trade is also observed to have increased, suggesting CBAM works like a tariff imposed by a trading bloc.

Similarly, there is a global loss of $3.4 billion in real income as a result of introducing CBAM. The brunt of it is borne by Oceania, India, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Ukraine, South Africa, and the Middle East. The EU on the other hand gains from positive terms of trade effect. While the effect of CBAM on employment is minimal in most countries, countries including Saudi Arabia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan can experience higher unemployment since the majority of exports to the EU are CBA products.

These three case studies—the US-China trade war, India’s Aatmanirbhar Bharat initiative, and the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism—were selected for their diversity in terms of motives, mechanisms and relevance. They illustrate distinct forms of protectionism: one driven by geopolitical and economic rivalry, another by domestic resilience and post-pandemic recovery, and the third by climate-driven trade regulation. Each case is evaluated on the basis of its impact on trade, investment and other broader consequences, allowing for a comparative analysis that captures the evolving landscape of protectionist policies in the 21st century.

6. Policy Recommendations

6.1. Diversify supply chains

Protectionist policies, particularly when they develop into trade wars, have lasting effects on international trade, investment, and income. What started as US tariffs on Chinese goods and China’s retaliatory tariffs on US goods escalated to a trade war partly owing to their overdependence on each other’s markets and supply chains. One way to prevent extreme shocks is to diversify the supply chains to avoid overdependence on any country. This can help mitigate the effect of barriers to a much smaller scale than desired. Additionally, it can promote developing economies such as Vietnam, India, Indonesia, and Mexico, increasing employment and income.

6.2. Promote domestic production without penalizing imports

India’s Aatmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan is a prime example of promoting domestic growth without damaging trade relations. Introducing measures to increase investment, provide employment, and create a conducive environment for startups will automatically lead to a more favorable trade balance and stronger economy. On the other hand, trade barriers often invite retaliatory measures that spiral into trade wars that adversely impact all countries involved.

6.3. Strengthen regional trade agreements

Regional trade agreements (RTAs) define common rules of trade to ensure smooth trade between two or more countries. Recently, RTAs have expanded their scope beyond tariffs and border agreements to include competition policies, government procurement rules, and intellectual property rights. When designed efficiently, RTAs are a powerful tool for all parties involved as it reduces trade costs. Deep RTAs have increased goods trade by 35%, services trade by over 15%, and global value chain integration by more than 10% (World Bank, 2018). The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) are some of the most prominent RTAs of the current global economy.

6.4. Strengthen the World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization established in 1995 to liberalize global trade, has since increased global income by $510 billion. It also stopped the 2008 financial crisis from spiraling into another great depression by preventing retaliatory protectionist measures between countries (Ihekweazu, 2011). However, changing dynamics have rendered the WTO ineffective. The WTO has been unable to facilitate an agreement on agricultural goods, the two biggest economies, the US and China, are engaged in a ruthless trade war, and the Appellate Body has been inoperative since 2020 (Peres, 2024). Countries should cooperate to strengthen WTO, establish common rules for smoother trade, aid developing economies by leveling the playing field, and introduce economies of scale through specialized production.

6.5. Exclude LDCs and LICs from CBAM

While carbon price is an effective way of encouraging less carbon intensive manufacturing, policies like CBAM that apply it on imports can exacerbate income inequality between countries. Switching to clean energy is more expensive for low-income countries (LICs) and least developed countries (LDCs), and would compromise their growth to pay the price of a global situation created by more developed countries. For example, the economy of Mozambique is heavily reliant on aluminum exports which is covered by CBAM. Excluding LDCs and LICs from CBAM would level the playing field by placing greater responsibility on the major historical contributors. In fact this would increase the exports, trade, and employment of LDCs and LICs, boosting economic growth and development (UNCTAD, 2021).

6.6. Impose the higher cost of carbon in imports on consumers

The high income and standard of living enjoyed by the developed countries came about as a result of industrialization with no regard for the environment. This has led to global warming and climate change in the present day. Rather than taxing the developing countries to keep the situation in check, the price of carbon must be charged on consumers in developed countries to shift demand to more sustainable choices. This will enable a lasting and positive demand side change while not punishing developing countries.

7. Conclusion

Protectionism seeks to restrict global trade through tariffs, quotas, and other government regulations to protect national security, safeguard and promote domestic industries, or push back against globalization. However, protectionist policies are often met with retaliatory measures that lead to a fall in global trade, income, investment, and growth. Such dynamics can also spiral into trade wars, as observed in recent years in the case of the US and China. In other instances, policies like the EU’s CBAM contribute to a better environment, but at the cost of the growth of developing nations. India’s Aatmanirbhar Bharat is perhaps one of the examples of balanced protectionism where domestic industries are promoted through greater investment and government support while international trade is not penalized and, in fact, welcomed.

Greater global cooperation and accountability are imperative for a conducive environment to global trade. This can be facilitated by strengthening RTAs and multilateral institutions such as the WTO, diversifying supply chains, and actively supporting domestic industries rather than restricting imports. As far as protectionist policies to push climate action are concerned, developed countries must take accountability for the environmental destruction caused by them and bear the cost of preventing exacerbation of the situation while letting developing countries, particularly LDCs and LICs, pursue economic growth and development. As we move forward, aligning trade policies with equitable climate goals and inclusive frameworks will be key to fostering a resilient and sustainable global economy.

References

A European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Implications for developing countries. (2021). [online] UNCTAD. Available at: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/osginf2021d2_en.pdf.

Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan| National Portal of India. (n.d.). https://www.india.gov.in/atmanirbhar-bharat-abhiyan

Barattieri, A., Cacciatore, M., & Ghironi, F. (2021). Protectionism and the business cycle. Journal of International Economics, 129, 103417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2020.103417

Brown, C. and Wang, Y. (2023). Five years into the trade war, China continues its slow decoupling from US exports | PIIE. [online] www.piie.com. Available at: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/five-years-trade-war-china-continues-its-slow-decoupling-us-exports.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. (n.d.). Taxation and Customs Union. https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en

Cato.org. (2022). Available at: https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/protectionism-or-national-security-use-abuse-section-232.

CFR.org Editors. (2025, April 14). The contentious U.S.-China trade relationship. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/contentious-us-china-trade-relationship

Dabrowski, M. (2024). The risk of protectionism: What can be lost? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17080374

Economic Nationalism is quintessentially fundamental to our economic growth; import only what is unavoidably essential, stresses the Vice-President | Vice President of India | Government of India. (n.d.). https://vicepresidentofindia.nic.in/pressrelease/economic-nationalism-quintessentially-fundamental-our-economic-growth-import-only-what

European protectionism: causes, motives, and consequences. (n.d.). https://trendsresearch.org/insight/european-protectionism-causes-motives-and-consequences/?srsltid=AfmBOorKJq4gZvakzzL3W0lT7JkyJM9d1b_FhGAx4OzGEomoHeYouths

Fajgelbaum, P. and Khandelwal, A. (2021). The Economic Impacts of the US-China Trade War. [online] National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w29315.

Fajgelbaum, P. D., Goldberg, P. K., Kennedy, P. J., & Khandelwal, A. K. (2019). The return to protectionism*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz036

Giordani, P. E., & Mariani, F. (2020). Unintended consequences: Can the rise of the educated class explain the revival of protectionism? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3534497

Gregori, T. (2020). Protectionism and international trade: A long-run view. International Economics, 165, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2020.11.001

Kapustina, L., Lipková, Ľ., Silin, Y., & Drevalev, A. (2020). US-China trade war: causes and outcomes. SHS Web of Conferences, 73, 01012. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20207301012

Meltzer, J. P. (2011, April 19). The Challenges to the World Trade Organization: It’s All about Legitimacy. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-challenges-to-the-world-trade-organization-its-all-about-legitimacy/

Mullen, A., & Mullen, A. (2022, July 6). Explainer | US-China trade war: timeline of key dates and events since July 2018. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3177652/us-china-trade-war-timeline-key-dates-and-events-july-2018

Online, E. (2023, May 16). India is fighting a war with its defence imports. Is it winning? The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-is-fighting-a-war-with-its-defence-imports-is-it-winning/articleshow/100280582.cms?from=mdr

Parsapour, D. & Institution for Economic history and International Relations. (2024). US-China trade war: causes, impacts and the unclear future of bilateral relations. In A. Malaki, Examensarbete 30 Hp /Degree 30 HE Credits International Relations Master’s Program Globalization Environment and Social Change [Thesis]. https://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1865800/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Peres, A. (2024). WTO: Challenges and Opportunities. [online] House of Commons Library. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9942/.

Self-reliant India (AATM Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan) | IBEF. (n.d.). India Brand Equity Foundation. https://www.ibef.org/government-schemes/self-reliant-india-aatm-nirbhar-bharat-abhiyan

Smith, A. (n.d.). Wealth of Nations — BK 4 ChPt 02. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/smith-adam/works/wealth-of-nations/book04/ch02.htm

Statista. (2025, February 13). Total value of U.S. trade in goods with China 2014-2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/277679/total-value-of-us-trade-in-goods-with-china-since-2006/

Sun, X. (2024). An exploration of the driving factors behind trade protectionism. Advances in Economics Management and Political Sciences, 59(1), 106–110. https://doi.org/10.54254/2754-1169/59/20231081

US-China trade war: economic causes and consequences. (n.d.). https://www.eurasian-research.org/publication/us-china-trade-war-economic-causes-and-consequences/

World Bank Group. (2023). Regional trade agreements. In World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/regional-trade-agreements

World Trade Organization protests in Seattle - CityArchives | Seattle.gov. (n.d.). https://www.seattle.gov/cityarchives/exhibits-and-education/digital-document-libraries/world-trade-organization-protests-in-seattle.

World Bank Open Data. (n.d.). World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG?end=2023&locations=CN&start=2015

Zhang, Z. (2024). Trade Protectionism and International Trade Policy Study. Frontiers in Business Economics and Management, 14(2), 115–119. https://doi.org/10.54097/p1dzhf35

{"@type": “Person”,"name": “Sinan Ülgen”}. (n.d.-b). A Political economy perspective on the EU’s carbon border tax. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/05/a-political-economy-perspective-on-the-eus-carbon-border-tax?lang=en¢er=europe

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.svg)

.svg)